UK Antarctic meteorite hunt bags large haul

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

The first British-led expedition to gather meteorites in the Antarctic has returned with a haul of 36 space rocks.

Manchester University’s Dr Katherine Joy was dropped in the deep field with British Antarctic Survey guide Julie Baum for four weeks.

The pair spent their days near the Shackleton mountains running across the ice sheet in skidoos looking for out-of-place objects.

The meteorites ranged from tiny flecks to some that were as big as a melon.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Some two-thirds of the meteorites in the world’s collections have been picked up in the Antarctic. It’s the contrast of black on white that makes the continent such a productive hunting ground.

“As soon as you spot a black rock you know. You dart towards it and your heart picks up a beat,” Dr Joy told BBC News.

“They look black because they’re burnt up as they come down through Earth’s atmosphere. They have a very characteristic exterior colour, and they have a kind of cracked surface where that exterior has expanded and contracted during the violent atmospheric entry.”

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester Other nations have long sent expeditions to the polar south to look for space rocks. The US and Japan have been doing it regularly since the 1970s.

China, South Korea, Italy, and Belgium also frequently despatch teams.

But this was the first all UK mission, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, and it means the 36 samples will all now come back to Britain for investigation.

Meteorites trace their origin to the asteroids and smaller chunks of rocky debris left over from the formation of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago. As such, they have much to tell us about the conditions that existed when the planets came into being.

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester Not only does the black-on-white contrast make for easier prospecting in the Antarctic, but hunters also get a helping hand from the way the ice sheet moves. Meteorites that crash in the continent’s high interior are buried and transported towards the coast, ultimately to be dumped in the ocean.

But if this conveyor happens to run into a barrier on the way – such as a range of mountains – the ice will be forced upwards and scoured by winds to reveal its cargo.

Expeditions will therefore concentrate their searches in these special “stranding zones”. And although the places visited by Dr Joy and Ms Baum had not been explored previously, they had very good reason to be optimistic when they set out.

The Manchester-BAS venture was a trial ahead of another deployment in the next field season that will try to target specific types of objects that seem systematically to be underrepresented in Antarctic finds. These are the iron meteorites.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

The irons come from the smashed up innards of early planetary bodies that grew big enough to have metal cores, just like Earth has today.

“When people search elsewhere, in the dry deserts of the Earth for example, they find a much higher proportion of iron meteorites,” explained Manchester mathematician Dr Geoff Evatt.

“It’s about 5%, whereas in Antarctica it’s about 0.5%. We’ve come along and said: ‘We think we can explain this statistical difference.'”

The hypothesis is that the distribution of objects is exactly the same in Antarctica – it’s just that the irons don’t come to the surface in the same manner as the stony meteorites.

The way metal conducts heat means any irons that rise upwards and encounter sunlight will soon melt their way back down through the ice.

Dr Evatt’s calculations suggest many of these objects should be just 30cm or so below surface.

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

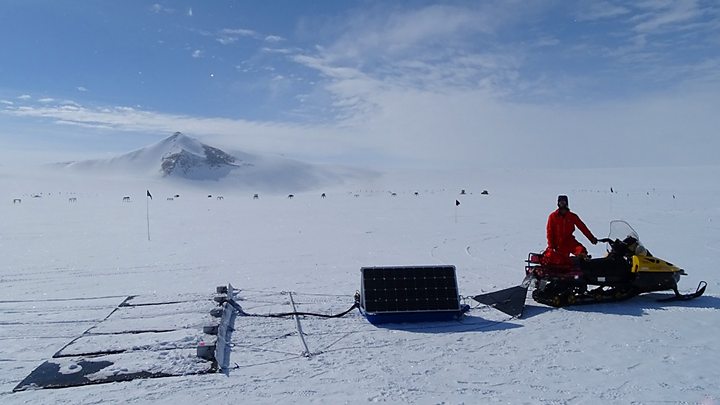

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester Which is why while Dr Joy was picking up stony space rocks in East Antarctica, he was in the west of the continent testing equipment that can look deep into the ice to sense the presence of metal.

“What we have done is design a wide-array metal-detector. It’s essentially a 5m-wide series of panels that we can drag behind the skidoo,” he said.

“In real-time, we’re able to sense what’s going on underneath the surface of the ice. And if an iron object passes under the panels then some lights and some audio equipment flashes up on the skidoo and we can then go out and hopefully retrieve the meteorite that’s within the ice.”

Dr Evatt tested the system at a location called Sky-Blu, which has similar ice to meteorite stranding zones but is much nearer to the engineering assistance of BAS’s big Rothera station than Dr Joy’s far-off search sites.

The array worked well and the team will take it to the Arctic next month for some final tweaks before using it in anger in just under a year’s time.

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester But even if this “missing meteorite” hypothesis doesn’t work out, Dr Joy believes her new hoard of space rocks demonstrates the value of regular expeditions.

“I would hope that we’ve validated the idea that going to Antarctica to collect meteorites in the places that BAS can get us to is working well,” she told BBC News.

“I’d like to think the people who are funding environmental science and space science will see this as a long-term opportunity for the UK.

“Potentially what’s out there are unique meteorites that come from bodies we’ve not yet visited with space missions, or unique pieces of Mars or the Moon that unlock untold secrets about how those planets have evolved.

“I’d like to take more people down, train the scientists how to collect meteorites safely and bring them back to the UK for research.”

Dr Joy’s own collection isn’t yet back in Manchester. The rocks are are taking the slower route home by ship. The box should arrive in the city in June.

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester

Image copyright Katherine Joy / University of Manchester BBC Radio 4’s Today programme will join the team next month in Svalbard for final testing of the detection equipment.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos