Early fish tapeworms found at ‘Britain’s Pompeii’ Must Farm

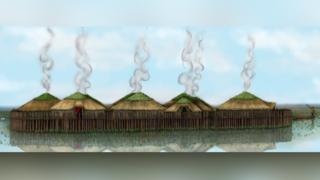

Image copyright V Herring/Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Image copyright V Herring/Cambridge Archaeological Unit The earliest evidence of fish tapeworm in Britain has been discovered preserved in human faeces, according to experts at Cambridge University.

The finds were unearthed at a site dubbed “Britain’s Pompeii”, a burnt-out 3,000-year-old village at Must Farm in Cambridgeshire.

Fish tapeworm can grow up to 10m (32ft) long and live coiled in the intestines.

The university said the research offered the first clear understanding of prehistoric Fen people’s diseases.

Cambridge University’s Dr Marissa Ledger said it also appeared they shared food with their dogs, because both were infected by similar parasitic worms from eating the raw fish, amphibians and molluscs.

Experts from the Cambridge Archaeological Unit at the university said they believed the “exceptionally well-preserved” village was just a few months old when it burnt down.

Circular wooden houses built on stilts, pots with food still inside, jewellery and evidence of fine fabric-making were just some of the finds unearthed during the 10-month long dig in 2016.

In addition waterlogged “coprolites” – pieces of human faeces – were discovered preserved in the surrounding mud, according to a study published in the journal Parasitology.

Teams from Cambridge and Bristol universities used microscopy techniques to detect ancient parasite eggs within the faeces and determined whether it was from a human or dog.

Evidence for Echinostoma and giant kidney worms was also discovered, during months of analysis since the dig was completed.

The researchers said little was known about the intestinal diseases of Bronze Age Britain.

A previous study of a farming village in Somerset found evidence of parasites spread through the contamination of food by human faeces.

This was less evident at Must Farm, possibly because waste was disposed of into the water around the marshy settlement.

Dr Ledger said the research “enables us for the first time to clearly understand the infectious diseases experienced by prehistoric people living in the Fens”.