Do party election broadcasts matter any more?

On the anniversary of the first appearance of the campaign tool on our screens, we look at their impact. …

Media playback is unsupported on your device

From sombre money box lectures to cheesy boy band spoofs, the party election broadcast has become a stalwart of our TV listings.

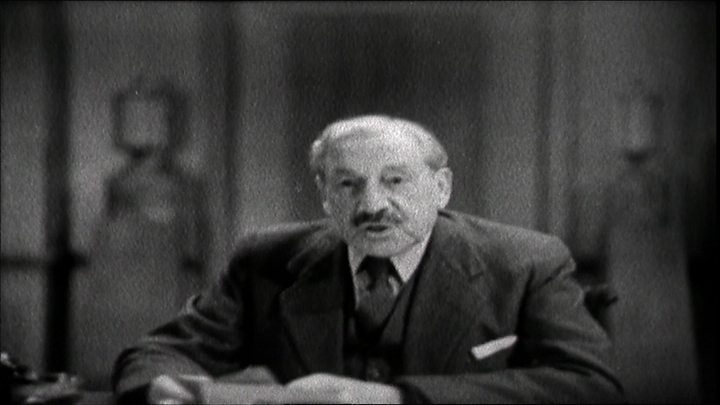

It was on this day – 15 October – in 1951 that former Liberal leader Lord Herbert Samuel took to our screens for the first ever televised version and changed political campaigning forever.

His appearance was a 15-minute slot, sat at a desk and staring down the camera lens, and reports at the time called it a fiasco as he read from a prepared radio script.

But despite that stilted start, within a decade, prime-time broadcasts had become an essential part of electioneering.

Technology – and the imaginations of communications directors – has, of course, moved on, and the rather formal broadcasts of old have morphed into more elaborate, faster-paced affairs.

But what is their impact? And will that continue in the future?

The history

The first party election broadcasts took place on BBC Radio during the 1924 election, with leader of the Liberal Party Herbert Asquith, Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin and Labour leader Ramsey MacDonald, each giving a 20-minute speech to the public.

It was another 23 years before they began to be regulated by the Committee on Party Political Broadcasts, deciding how long each party would get on the airwaves.

But come the launch of BBC Television, the slots made their way to screen.

And in 1955, with the emergence of commercial television, the broadcasts spread to more channels, and by 1959 they were part and parcel of an election campaign.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Lord Peter Mandelson – a key player in Tony Blair’s Labour government – said the broadcasts went through a “transformative” process in the 1980s, when his party’s then-leader, Neil Kinnock, brought in a famous face to make one.

Chariots of Fire director Hugh Hudson made what is known as “Kinnock: The Movie” – a move Lord Mandelson said was “trailblazing”.

But the Labour Party was not alone as political outfits from across the spectrum ramped up their game.

Kevin Pringle, the director of communications for the SNP until after the 2015 general election, said his party made big changes in the same decade, creating a soap opera series for one campaign and even a quiz show format for another.

“Perhaps when you look at them now, they are not so impressive,” he admitted. “But back then, they were considered cutting edge.”

The new formats – and use of celebrities – have continued since, as parties still compete over their showing on the main channels.

It is still down to those channels – which now form the Broadcasters Liaison Group – to decide what length of airtime they want to give each.

But Ofcom sets the rules for the broadcasts, which include the fact a party must be contesting at least a sixth of the seats in the election to qualify for a slot. They must also have a running time of either two minutes 40 seconds, three minutes 40 seconds, or four minutes 40 seconds.

Do they have an impact?

The short political slots on television may have more to compete with now, and viewing figures for all strands of television have taken a hit.

But research from Neuro-Insight said these particular broadcasts still had an “considerable influence” over viewers’ perceptions of political brands.

And Mr Pringle said having those few minutes on prime time TV can make a big difference to a party’s reach.

“TV is such an important medium – and the biggest – and if you are not on it, you are not at the races,” he said.

The former communications director said the broadcasts had their challenges, as they needed to be good television viewing, as well as holding a strong political message.

But they provide a “guaranteed mass audience… which every party wants”, he added.

Alastair Campbell, the director of Mr Blair’s campaigns – who worked with him in No 10 – said the broadcasts were also good for the party machines.

“It can boost the moral of the campaign when done well,” he said. “And if they are done properly, they can get extra coverage in the media for the party.”

Media playback is unsupported on your device

For Sir Bernard Ingham – Margaret Thatcher’s longest serving press secretary – broadcasts are a good platform to set out policies, but you need the plans to back them up.

“It’s an opportunity that no party would turn down,” he said. “But I think [their success] depend on the content of those policies.”

Baroness Olly Grender, who was the deputy director of communications for the government during the coalition – working for Lib Dem leader and deputy PM Nick Clegg – also said the broadcasts had a “real value” for voters.

“The alternative is to have attack adverts like the do in the US, which is not a route we want to go down,” she said.

“Having been in the US during an election, [UK] broadcasts add to political knowledge, which those adverts don’t.”

What about the future?

Westminster is in agreement that an election is looming – perhaps even by the end of the year – so expect more broadcasts to hit your screens in the coming months.

These traditional post-teatime news slots make up for the ban the parties face on buying other TV and radio advertising.

However, as the Electoral Commission has pointed out, “electoral law was written long before campaigning went digital”, so rather than one channel with one guaranteed audience, you are looking at internet advertising with spending on the rise across multiple platforms – especially social media.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Mr Campbell said TV broadcasts were still important, “even if they are less so now”.

“If the broadcasting rules allow for parties to get a few minutes of prime time… you would be foolish not to take them, as there are potentially millions of people watching,” he said.

And when it comes to social media, he believes the broadcasts are “part of the same thing”.

“Look at Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn. They are relentlessly pumping out something on social media, but these [broadcasts] give you four or five minutes more and form part of the strategy.”

Sir Bernard believes the scope of influence for the TV broadcasts has diminished as a result.

“I am sure some people suffered if they went wrong, but there are so many voices now that people are switching off,” he said. “I don’t watch much television myself.

“They are a means, but only one, and God knows, there are so many now.”

Mr Pringle agreed there were other outlets to spread policies, but that did not take away from the party election broadcast.

“Of course there are many other things now, like social media, but many parties use those tools to spread their political election broadcast further,” he said.

“I think the political election broadcast will be here for many years to come.”