Long waits ‘leave mental health patients in limbo’

NHS leaves patients stuck on ‘hidden’ waiting lists for months, a BBC investigation shows. …

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Patients with mental health problems are being left in limbo on “hidden” waiting lists by England’s NHS talking therapy service, the BBC can reveal.

The service – called Improving Access to Psychological Therapies – provides therapy, such as counselling, to adults with conditions like depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.

It starts seeing nine in 10 patients within the target time of six weeks.

But that masks the fact many then face long waits for regular treatment.

Half of patients waited over 28 days, and one in six longer than 90 days, between their first and second sessions in the past year.

For most, the first session is a combination of an assessment and basic advice, with the second appointment marking the start of the core treatment sessions.

Charities said the headline target was giving a false impression of what was happening, warning that patients were facing “hidden waits” that were putting their health at risk.

NHS England acknowledged the pressure on the system was causing delays, but pointed out that despite the delays, half of patients given treatment still recovered.

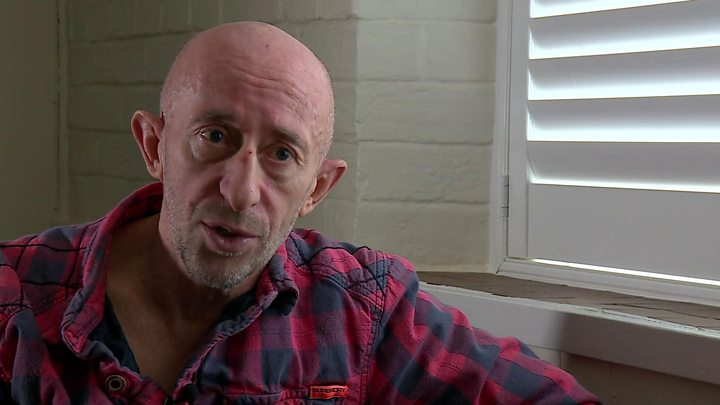

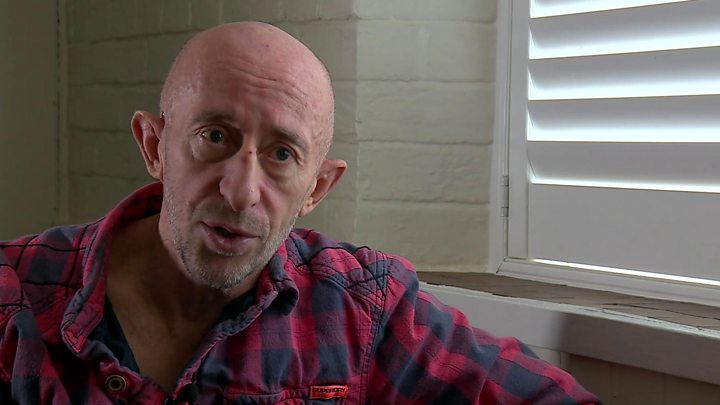

‘I tried to kill myself while I waited’

Paul Williams, 60, was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder following a violent incident he was involved with as a police officer in Devon.

He had to retire on medical grounds from the service in 2013 and turned to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) for help.

While waiting for therapy, he tried to take his own life.

“The treatment was really good when I got it, but the problem is you are kept in a holding pattern.

“Waiting is really hard when you are struggling mentally.

“I’m not saying the delays were the reason I tried to kill myself – I had lost my career and there was a lot going on – but they certainly didn’t help.”

‘I had to pay for private treatment’

Gemma, 30, a teacher from Portsmouth, is another patient who turned to the service when she was suffering panic attacks and anxiety two years ago.

Demands on the service meant face-to-face therapy was not available quickly, so she ended up paying for treatment privately.

She said: “It’s such an important service, but it was not there when I needed it.

“I fear people’s lives are being put at risk by this.

“I was having suicidal thoughts and knew I needed seeing quickly.

“It cost me £60 a session. I had them every week for three months.”

How long are people waiting?

Like many NHS services, IAPT is expected to see patients quickly. It has been given a target of seeing 75% within six weeks of a referral.

It achieved this in nearly 90% of cases in 2018-19.

But it is the second appointment which kick-starts the regular treatment for most patients.

This normally starts with weekly sessions before becoming less frequent.

The numbers facing long waits for the second session have been growing.

During 2018-19, of the 580,000 patients who went on to have a second session, half had waited more than 28 days from their first appointment for it.

One in six patients – nearly 95,000 – waited over 90 days, a doubling in number in just three years.

That is on top of their wait for the first appointment. The average overall wait from referral to second session is over two months.

The impact on patients

There is concern that the delays are leading to patients dropping out.

Data analysed by NHS England suggests there around 100,000 patients a year who drop out between the first and second appointment, who need treatment.

It is not known, however, just how many of these would be down to the waits.

Marjorie Wallace, chief executive of the mental health charity Sane, said the findings “gives the lie to current waiting time figures being a mark of success”.

She said the fact that so many patients were facing these “hidden waits” was “deeply concerning”.

“We fear these delays may leave some people more at risk than they were before.

“During the period the person is being assessed as needing help, their expectations are raised, only to be disappointed and lose faith that help is there.

“If that critical window passes, then it may be too late. Such experiences may trigger a patient into self-harm, or increase the risk they become suicidal.”

Paul Farmer, of the charity Mind, agreed. “IAPT has been the biggest driver of more people getting access to services over the last ten years.

“But there are problems. Being left without support can have life-threatening consequences.

“Whoever forms our next government needs to make sure that everyone with a mental health problem gets the right help and support at the right time.”

Why is this happening?

IAPT has certainly been a victim of its own success.

The numbers being referred into the service have been rising ever since it was launched.

Last year more than 1.5 million referrals were made – up by more than 10% in a year.

Most do not end up being given a course of treatment.

But individual services have still reported there is a shortage of therapists to provide support to the growing number of patients.

Steps are being made to tackle this. NHS England acknowledged there were pressures in the system and said it was now providing financial support to local services to cover the cost of training extra staff.

But a spokesman said the service was still exceeding expectations, and helping “hundreds of thousands overcome” their problems.

The spokesman said seven in 10 patients show a “significant” improvement in their condition, with half going on to recover so that they were no longer clinically classed as having a mental health problem.

Although these figures have been questioned. In November, BBC Five Live Investigations Unit discovered that IAPT success rates were in some instances being manipulated by its staff in the private sector.

Multiple IAPT practitioners in private sector organisations contracted to roll out the service detailed their experiences of guiding patients through patient assessment questions to ensure success rates were met.

NHS England said such cases should be raised with them as “falsifying scores is unacceptable”.

The other UK nations also have their own NHS talking therapy services, but it has not been possible to tell whether similar problems exist.

Data analysis by Clara Guibourg and Edwin Lowther