Man Utd v Man City: The schools teaching future stars for both clubs

As Manchester United and Manchester City meet in Saturday’s FA Cup final, BBC Sport looks at the schools which specialise in…

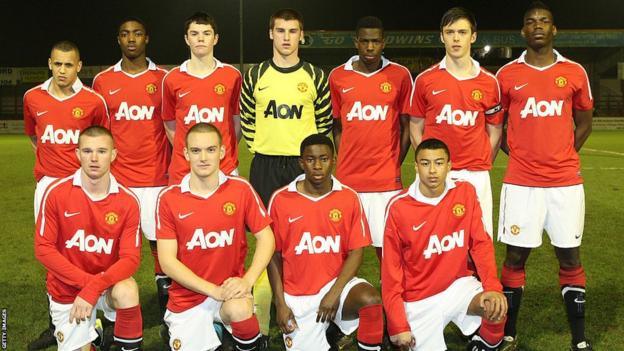

Arms over shoulders, smiles breaking across fresh faces, marker-pen messages scrawled on white shirts.

The photo is one like many others at this time of year, as schools break up and futures slowly come together.

Except this photo is slightly different. These are four ordinary schoolboys with extraordinary careers in front of them.

On the left is Tosin Kehinde, who now plays for Randers in the Danish top flight. In the centre is Jimmy Dunne, a regular in QPR’s defence this season. On the right is Axel Tuanzebe, who has spent the past six months as part of Stoke’s squad.

At the front, is the most familiar face; Manchester United star Marcus Rashford.

The photo was taken at Ashton on Mersey School, where batches of United’s academy prospects have been walking the corridors for 25 years.

It is a school where future stars are today’s students.

And it isn’t the only one in Manchester.

“Many, many, many of our boys will stay at their own schools,” says Nick Cox, Manchester United’s academy director, and a former teacher himself.

“We will build amazing relationships with those schools to make sure we are communicating regularly and dovetail their programme with ours.

“I am a big believer that you stay at home, with your family, in your own bed, with your mates at school for as long as possible.”

Sometimes, though, as players get older, as they join the academy from further afield, as their football becomes more time-consuming, it makes sense to switch to a school set up for the demands on an aspiring Premier League star.

Manchester Grammar School, a private school that partnered more recently with United, is half an hour’s drive from United’s Carrington training ground.

But Ashton on Mersey, a state school in Sale, is closer and takes on more of the club’s prospects.

The link is the longest such relationship in England.

David Law, former head of PE at Ashton on Mersey, saw how it started and how it blossomed.

“It came out of the specialist college initiative in the late 1990s,” he remembers.

“Ashton on Mersey wanted to be a sports college, but you needed £100,000 of private sponsorship. A lot of schools were scrabbling around for the money.

“I went to a conference down in Loughborough, where they mentioned that a lot of Premier League clubs were looking to link up with schools.”

Law was a Manchester City apprentice in his youth. He remains a City fan. But a contact from his days coaching local youth teams was at United.

He put in a call. Soon afterwards, he found himself in a meeting.

“There was the headmaster and United finance director David Gill and, at the end, United wrote a cheque for £100,000,” Law says.

The investment was a good one.

Less than five years later, on a Thursday morning in March 2003, Law had to hurriedly change his lesson plan.

“Darren Fletcher had made his debut as an 18-year-old the previous evening in the Champions League against FC Basel,” Law remembers.

“He had played really well, and he didn’t sleep when he got home because the adrenaline was still flowing thorough his system.

“But the next morning, he was in school on time for 08:45. I actually stopped the lesson so that he could talk to the kids about his experiences the night before. He was a lovely lad, a great character.”

Rashford was similarly punctual on a Monday in February 2016.

The day before, the 18-year-old had scored two goals in a 3-2 win over Arsenal. Timothy Fosu-Mensah, another Ashton on Mersey pupil, had also made his Premier League debut in the game.

“I walked into the sixth-form common room on Monday morning, before lessons began, and Marcus Rashford was playing pool with one of the other sixth-form boys,” the school’s headteacher, Aidan Moloney, told the Telegraph at the time.

“Marcus and Tim wanted to be at school on Monday. They wanted to be around their friends.

“The staff went over to congratulate Marcus and Tim, and then at 09:00, the bell went and they were straight down to lessons.”

Picking St Bede’s College’s greatest contribution to Manchester City’s history may be a question of faith.

On a Sunday morning in May 2012, then-manager Roberto Mancini walked into the school’s chapel, sat in a pew and prayed.

A few hours later, Edin Dzeko and Sergio Aguero scored against Queens Park Rangers in injury time; completing a miraculous turnaround and securing City their first league title in 44 years.

St Bede’s role in delivering Phil Foden to the first team is more definite.

Foden moved to St Bede’s from Stockport Academy at the age of 12.

The private school, a mile from City’s former Maine Road home, has been partnered with the club since 2011, and, while Foden is the most successful product, there have been plenty of others.

Cole Palmer, Taylor Harwood-Bellis and Tosin Adarabioyo, now with Fulham, are all former pupils who have gone on to play for City at senior level.

The arrangement has also, inadvertently, strengthened United’s ranks.

Jadon Sancho and promising youth prospect Charlie McNeill – who attended St Bede’s as City Academy prospects – have crossed over and now represent the red half of the city.

City, like United, have partner schools in both state and private sectors; some of their prospects attend Barlow RC High School in the upmarket suburb of Didsbury.

But most flow from St Bede’s to the City Football Academy (CFA) where the youth teams train in sight of Etihad Stadium.

“I used to do half days and then do training,” said Foden in 2022 of his time at St Bede’s.

“It was really enjoyable because we would look forward to dinner time when we would get on the coach outside to go to training.”

The day-to-day is timetable is a bit more varied than Foden describes – even players in City’s under-16 team do two full schooldays a week learning at St Bede’s.

But City have a useful ability. As well as bringing their boys to a school, they can bring the school to their boys.

There are eight classrooms at the CFA and St Bede’s teachers will make the trip alongside their pupils so they can deliver lessons around training.

The academic expectations are the same as for any other pupil. If City’s players receive a detention at school, they miss training at the club.

In summer 2021, 97% of City’s Academy players at St Bede’s achieved at least four C-grade from their GCSEs, while 38% achieved seven A grades or better. Both figures are well above the national average.

However, Foden has suggested that, for him at least, the focus occasionally slipped away from the books.

When St Bede’s tweeted to congratulate the then-18-year-old on becoming the youngest Englishman to score in the Champions League back in November 2019, he jokingly replied that the goal justified his skipping homework.

Meeting standards in the classroom is one challenge, fitting in with new school-mates is another.

Some young players are not just striving to beat the odds and make it as a professional, they are getting used to being in a new country all together.

Paul Pogba, Gerard Pique and Giuseppe Rossi are among the teenagers who attended Ashton on Mersey after moving to the UK at a young age to join United’s set-up.

They had the chance to work with a tutor to get their English up to speed, and lived with local families, some on Cecil Avenue, the same road as the school, to make things as easy as possible.

City have a transition process for new St Bede’s pupils, which can take several months and multiple meetings between the school, family and club in a non-football context.

To help the young City players settle in and not stand out, St Bede’s reportedly does not allow them to wear club-branded coats.

It is difficult, though. The prestige of a Premier League club can cause ripples in a school’s social life.

“I think it was mixed really,” said Law of other pupils’ reactions to the arrival of United prospects at Ashton on Mersey in the early years of the partnership.

“I think some of the lads might have been a bit jealous seeing these potential superstars walking about.

“Having said that, the girls at the school were mad for the boys really. I think one or two relationships developed from it.”

Rashford is in one of those relationships. He is engaged to a fellow former pupil.

Whatever the buzz caused by their presence, Cox says United’s aim, for a large part, is to stay in the background of a young player’s life.

“We can’t dominate their lives,” he says. “We can’t create a world where their sole identity is being a footballer.

“I want the boys to be normal. They will put the uniform on, they will be taught with all the other kids and they will be encouraged to integrate into extra-curricular activities. We want them to be in the school play, to learn how to play the violin and all those things.”

It seems to work. Jesse Lingard was Ashton on Mersey’s deputy head boy in his final year at the school. Ravel Morrison would work alongside Law to deliver PE lessons to younger kids, demonstrating a range of sports.

However, the area of school life where – in theory – academy kids could most easily get involved, is actually the trickiest.

City’s players don’t play for St Bede’s football team. It is felt it would be unfair to other pupils at their school and opposition teams alike.

United’s policy is more open. There have been players in their under-16s side who squeeze school football, cricket or rugby games into a packed schedule. But it is rare.

Athletics, requiring less co-ordinated practice with team-mates and no contact, is often a good compromise.

City players were part of St Bede’s team at a recent Manchester-wide schools championship.

In 2014, Ro-Shaun Williams, who would take on Rashford and Tuanzebe in post-training races at Carrington, clocked 10.99 seconds for the 100m, breaking a 25-year-old Ashton on Mersey record held by Olympic silver medallist Darren Campbell.

Defender Williams, who played a number of friendlies for United before leaving in 2019, is now at Doncaster.

Cox emphasises that wherever his charges go to school, whatever they do while they are there, their learning continues well out of the classroom.

United put on cookery lessons for their players, teach them how to manage their finances and cover advanced driving lessons. They learn the history of the club and the world beyond. One group recently visited Auschwitz to understand the significance of the Holocaust.

Today, some of them will be at Wembley to watch their first-team counterparts in the FA Cup final against City.

“They need to look back on our programme and think ‘that was incredible, it has enriched my life’,” Cox says. “Part of that is creating memories that our kids will remember forever.

“By being committed to our football programme, they will learn a lot about having purpose in their life, they will be fit and healthy, they will travel the world, they will meet interesting people, they will be disciplined, they will learn how to be punctual, they will be really good communicators, they will be committed to learning.

“Everyone leaves the academy. Some leave for the first team, some leave to other first teams, some leave for wonderful jobs outside of football.

“It is important to me that at the end of this journey, if they become a footballer or not, that they have maximised their potential.”

Whether they swap their graffitied school shirt for a United shirt, City shirt, or neither, each leaver departs with lessons learned.