Len Bias: The NBA draft star and his overdose – a death that changed America

Len Bias turned from feel-good story to cautionary tale in the space of two fateful days in 1986. The young basketball…

Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and find the most recent in the series here.

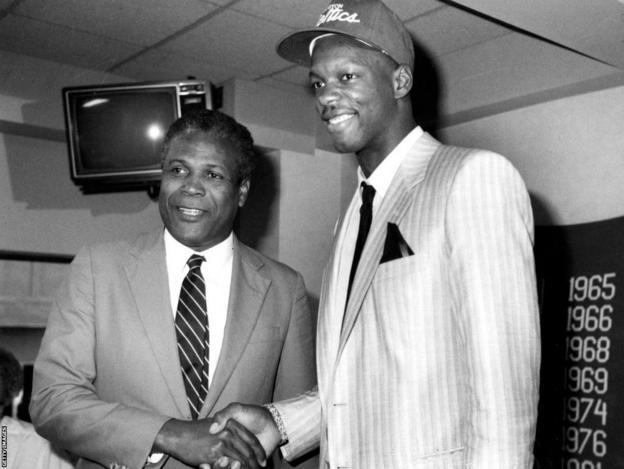

Dressed in an all-white suit, sitting next to his father in a room full of hope and anxiety, basketball player Len Bias had been waiting for this moment his whole young life.

At the NBA draft of 1986, Bias was 22 years old. He was 6ft 8in and weighed 15st (95kg). Pundits had already labelled him the best prospect around – better even than 1984’s third pick, Michael Jordan.

Bias duly went high and early. His name was called out second. The Boston Celtics, who had just won a second NBA Championship in three years but secured an early pick via a deal with the Seattle Sonics two years earlier, added him to their roster.

The green Celtics cap thrust into his hand represented ambition and expectation for a side built around ageing champions.

As wild cheers rung out, he hugged his dad before striding up on stage to shake NBA commissioner David Stern’s hand, cameras trained on his every move.

Grainy film shows a glimpse of how Bias had built his reputation to this point. He had already mastered a silky-smooth jump shot other players spend years crafting. He was explosive, athletic, destined for superstardom – it should have been just the start of the showreel.

Instead, short clips are all we have. Two days after being drafted to the Celtics, Bias died from a cocaine overdose.

His death shook basketball, but the reverberations went far further, touching America’s street corners, courtrooms and highest offices for years after.

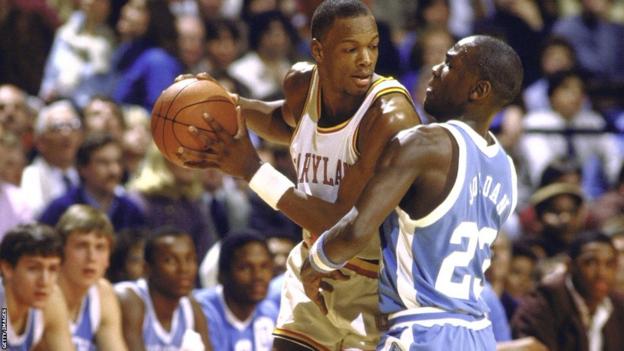

Bias drifts wide, unnoticed by the defence, and calls for the ball. His team-mate Jeff Adkins spots him and floats the ball towards the rim. One of North Carolina’s finest, Brad Daugherty, a future NBA all-star, is under it. But Bias, still a freshman, is too strong, too explosive. Bias soars above Daugherty, seizes the ball and buries it through the hoop in a single, smooth movement.

The Washington Post journalist watching in the stands described Bias “defying physics by hanging in the air for about three seconds, and unleashing a 20-megaton dunk that sent the overflow crowd rocking in ecstasy”.

It is perhaps the most memorable moment from Bias’ most memorable game. It came in February 1983, when Bias, playing for Maryland University, took on the University of North Carolina and their own phenomenon, Jordan.

Despite being a 19-year-old in his first year on the team, Bias struck the more impressive figure, bigger and more athletic than Jordan, and a potentially more dominant force on the court.

Jordan was already a certified star. He had landed the game-winning shot when North Carolina snatched a thrilling national title win the previous year. Bias, on the other hand, was just a freshman. But, as Maryland secured a 106-94 win, it was clear Bias was going to bring Jordan trouble.

As the era of Larry Bird versus Magic Johnson was drawing to a close, could this be the next rivalry for a new generation of basketball fans? Little did spectators know that Jordan and Bias would never get the chance to renew their rivalry on the professional stage.

Leonard Kevin Bias was born on 18 November 1963 in Landover, Maryland, a small town on the outskirts of Washington DC. He was one of four siblings who all attended the same elementary school, theatre school and high school.

“He loved creativity and could see the beauty in things that most people couldn’t,” Bias’ mother, Dr Lonise Bias tells BBC Sport.

“When he was in college, he loved interior design. He had that eye for putting things together and he was always meticulous about his appearance.

“He was the type of person who strived for perfection – he didn’t like stuff halfway. He liked order. As he was developing, he was able to discover the hidden abilities within him.”

You can see the creativity when you watch him on the court; inventive methods of getting the ball into the bucket, whether that was an assist to a team-mate through the legs of an opposing player, or shifting his body in awkward positions when flying to the rim. You could see Bias’ creativity spilling out on the court.

Bias had a growth spurt around the age of 13. Dr Bias says it was as if he had “grown a foot overnight”.

Playing on the junior high school team, he was known as ‘the human eraser’ because of the way he would block shots.

He had college offers from across the United States, but opted for Maryland to stay close to his home and family.

As a freshman, Bias lacked discipline, relying on his natural talent and balletic agility that had fellow students compare him to Muhammad Ali.

“You couldn’t talk to Lenny in his freshman year,” team-mate Ben Coleman said in 1984. “Criticism or advice would go in one ear and out the other.

“But that’s changed as he’s gotten older,” Coleman continued. “Len is going to be a helluva ballplayer.”

Coleman’s prediction and Bias’ potential was realised. During his four years at Maryland, Bias scored a mountainous 2,149 points, a school record at the time, and twice earned All-American honours, recognising the best young players in the country.

“He had a sweet jump shot,” says team-mate Keith Gatlin, who arrived at Maryland a year after Bias.

“He jumped so high when he left the air people would try to get to his elbow, but couldn’t because he was such a freak of nature.

“People were just in awe when they saw him because he was just a down-home, regular guy. But his talent was enormous.

“He didn’t know where he was going to go, but he was just excited to play and make basketball his profession.”

Gatlin saw Bias a couple of days before he set off for New York to attend the 1986 draft at Madison Square Gardens. Both men were overwhelmed by the idea that Bias was officially going to become an NBA player.

Joining the Celtics was a dream. A team flooded with talent: Larry Bird, Danny Ainge, Kevin McHale to name a few.

“They’re a good team,” Bias said in an interview immediately after he was picked. “I can go there and sit on the bench. Whether I play or not, I’m going to learn a lot from the players there.”

When Bias and his father made it back home to Landover, Maryland, he was met with overwhelmed hugs from family members. But his mother was not at home – she was at a work meeting.

Bias decided he would head back to his university campus to celebrate. Gatlin bumped into him as he entered the dorms.

“He was excited and really, really blessed,” Gatlin says. “He just smiled at the fact now he could do something that he’s been doing all his life, but get paid for it.

“He said ‘Look, I’ll see you in the morning. I’m going to get ready to see my mom and dad then I’m going to go visit a girl who I haven’t seen in a while, so I’ll see you in the morning and we’ll get some breakfast.'”

Gatlin agreed.

And that was the last time he saw him.

Bias did not go to see his mom and dad or visit the girl he had not seen for a while. Instead he decided to meet up with some other friends and make a quick trip to the liquor store. They bought a six pack of beer and a bottle of cognac and headed back to the dorm room next to Gatlin’s.

One of the group was Brian Tribble. Although Tribble had dropped out of the University of Maryland, he still hung around campus and had bonded with Bias over a shared love of basketball and music.

It is unknown whether that night was the first time Bias had tried cocaine. Certainly, many of those closest to him had no inkling.

Just before the 1986 draft his Maryland coach, Lefty Driesell, was asked what Bias was like off the court.

“All I can tell you,” replied Driesell, “is that Leonard’s only vice is ice cream.”

Gatlin was similarly unaware of any drug use.

“I’ve been out with Lenny many, many times and the thing that hurts me the most is that I never saw him touch drugs before. Never,” says Gatlin.

“So, to ‘know’ him and then to see what happened was something that I’ve never been able to wrap my head around. I don’t think I ever will because I never saw that side of him.”

Bias consumed alcohol and cocaine deep into the night, before he decided to lie down. The other three in the room thought he had passed out from partying. A couple of minutes later he started violently twitching.

Bias was having a seizure.

The 911 call was made by Tribble at 6:31am, distraught with fear and disbelief.

“This is Len Bias. You have to get him back to life. There’s no way he can die,” Tribble, himself heavily under the influence, said to the emergency operator.

“It doesn’t matter what his name is,” the operator replied as Tribble repeatedly brought up Bias’ name.

Gatlin, in the dorm next door, was woken shortly after by the phone.

“My mother called and said that she’d had a dream, and something was wrong,” he says.

“I said ‘Wow, well I’m glad you called me, I have a math class at 8am.’ She said ‘Are you sure everything is OK?’ I said ‘Yeah, I’m going to double check on my sister too.’

“When I went into the corridor to call my sister, I looked into the other room and saw my team-mates. I saw Lenny on the floor and that’s when I knew something had gone wrong.

“I just spoke with this person last night, and now I look down and I see him on the floor. I don’t wish on anybody what I saw right there.

“I just froze. I called his mother, woke her up and told her the wrong hospital he was being taken to because I was frantic. I woke up the rest of our team-mates and we followed the ambulance to the hospital.”

By the time his mother and father could make it to the correct hospital, Bias had already been pronounced dead.

“I did not know who Len was,” says his mother Lonise.

“I knew that he played basketball, that he was my son, and he was doing well. I didn’t know who he was as a man.

“It wasn’t until he died that I found out who he was.

“People around the world were grieving over the loss of this man and this was just my son that I love. I didn’t know the level of popularity he had until he passed.

“We received flowers from the president and other personal cards from the vice president of the country, from the Senate leaders, Michael Jordan sent flowers, Larry Bird, and Magic Johnson’s mother called.”

Maryland’s chief medical examiner attributed Bias’ death directly to cocaine. He said it had “interrupted the normal electrical control of his heartbeat, resulting in the sudden onset of seizures and cardiac arrest”.

Tribble was put on trial on charges of supplying the cocaine that night, but was found not guilty.

“I love Lenny Bias,” he said outside the courtroom. “I always have, always will.”

In 1990, three years later, Tribble would be convicted for 10 years for large-scale cocaine dealing.

Tribble’s conviction was just one of millions in the wider ‘War on Drugs’ that dominated the policies of successive US governments.

Between 1980 and 2009, the adult arrest rate for drug possession or use increased by 138% in the United States, with the majority of the rise in the first decade of that 30-year period.

Bias’ death, at his physical peak, with a future laid out before him, was part of the justification for harsher sentences for smaller amounts of certain drugs.

“Len Bias, he was the man – he was going to be the next superstar,” says historian David Farber, author of War on Drugs: A History.

“I grew up in Chicago, I grew up with Michael Jordan, but there were people saying ‘he’s going to take Jordan’. There was fear about Bias going to the Celtics, he was that good.

“The speaker of the House of Representatives at the time of his death was Tip O’Neill, who could see there was a mid-term election coming up in November 1986.

“He understood a whole lot of people were terrified that this superstar athlete, this extraordinary fit young man had fallen prey to a cocaine overdose. O’Neill represented Boston, was a Celtics fan. It was really good politics for him to pay attention to the specificity of Len Bias’ death.”

O’Neill, a Democrat, realised his party could not afford to be seen as weak on an issue that was seeping into the psyche of American voters.

“Time magazine and Newsweek were outlets that middle-class Americans would read at the time. They had massive circulations at this point and had begun to pump crack as the new American nightmare,” says Farber.

“Crack was not something whites, the middle class and suburban youths were using either. But it was a great ‘what if?’.

“Bias didn’t use crack, he died of a powdered cocaine overdose, but that’s not what people perceived at the time.”

O’Neill was the driving force behind the Anti-Drug Abuse Act that became more draconian the more it was discussed.

“This bill started to become a bidding war around who could punish drug dealers and drug users more,” explains Farber.

“Usually you negotiate – Labour and Capital, they find a way to fight and compromise.

“But on this there was no negotiation, it was like, ‘Let’s put them away for five years? No, let’s put them away for 10 years! Let’s reduce the amount of crack that puts you in jail from 100g to 50g! Actually, how about 10g?’

“Len Bias was in the centre of all of this. Here’s this superhero who becomes an emblem of what drug abuse can do to the best of us.”

In October 1986, a little over four months on from Bias’ death, President Ronald Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act into law in the White House’s East Room.

The act specified amounts of certain drugs that would trigger a prosecution for possession. For crack cocaine, the level was set at 5g. For powdered cocaine – the more expensive drug that had killed Bias – it was set at 500g. The minimum sentence for a conviction in either case was five years without parole.

It also set a minimum 20-year sentence for anyone convicted of dealing drugs that caused death or serious injury.

“This legislation is not intended as a means of filling our jails with drug users,” Reagan told the press.

But its effect was exactly that.

In 1986, the US prison population stood at 522,064. Ten years later, it was more than 1.1 million.

“It just started to take young people and throwing them into prison in massive numbers,” says Farber.

“Poor communities – in particular poor black communities – were hit really hard. Crack was a drug that was tailor-made for poor people because it was cheap, it created a really strong and immediate high, and it was reproducible again and again.

“In the United States, we talk about a carceral state, a state built around putting people in prison and that starts with the crack-cocaine hysteria.”

Bias’ death prompted two questions. One has been a source of fascination to basketball fans: what if he had a chance to play in the NBA? The second spread fear throughout America: what if this happens to our children?

Len’s mother, Lonise, would be entitled to more.

Less than five years after the loss of Len, his younger brother Jay was killed in a drive-by shooting.

However, she has found meaning amid the starkest adversity.

“My strength has been my faith,” she says.

“The heartache of losing a child is a hundred times worse than a parent can imagine. My belief system and my faith in Jesus Christ is how I have made it.

“For me, Len and Jay were two seeds that went down into the ground to bring forth life. They weren’t buried, they were planted, to bring new information and insight to another generation and encouragement to those that need it.”

Dr Bias now speaks around the world about healing, self-discovery and the power of community.

And when she thinks the last time she saw Len in person and in life – the day before he travelled to New York for the draft – she remembers only his enthusiasm.

“He was excited, excited, excited,” she says.

Excited for a future cut so cruelly short.