Concussion and sport: How the lives of ex-sportspeople have been affected by concussion

BBC Radio 5 Live speaks to former sportsmen and women and their families about how concussion has changed their lives. …

“Lots of anxiety, lots of depression. My eyes and my brain started burning when I looked at the phone screen.”

BBC Radio 5 Live has been speaking to former sportsmen and women and their families about how concussion has changed their lives.

It follows an MPs’ inquiry that said sports bodies are “marking their own homework” when it comes to reducing concussion in sport.

The inquiry, carried out by the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport select committee of MPs, says urgent action is needed by government and sporting bodies to address a long-term failure to reduce the risks of brain injury in sport.

This is what former sportspeople say…

‘Save players from themselves’

Rugby league player Stevie Ward, aged 27, had just been named Leeds Rhinos captain when his head was crushed in a pre-season friendly.

Two weeks later, he took another knock to the head which resulted in stitches in his face.

“After that, it was a horror show really,” he said. “Lots of anxiety, lots of depression. My eyes and my brain started burning when I looked at the phone screen.

“That was the forbearer for where I am now, 18 months down the line. Still struggling with migraines, still struggling with car sickness and sensitivity to screens and light, heat.

“I’ve retired, stopped playing and I’m just trying to make ends meet and transition into a new life.”

Ward told 5 Live’s Nicky Campbell that rugby players thrive off danger and risks, so the culture in contact sports needs to change to “save players from themselves”.

“Because we want to play a tough, physical, demanding game, there’s even more need for having doctors there, specialist and medical officers that save you,” he added.

Stevie’s partner Natalie Alleston said their life had been completely changed by those two games and they could no longer make long-term plans.

“We can try and put things in place… everything’s subject to change depending on how symptoms present themselves that day.”

‘You’re sliding headfirst on ice at speeds of up to 80 mph’

Eleanor Furneaux is a former GB skeleton athlete who was forced to retire at 24, after hitting her head.

In January 2018, while training for a race in Germany, a minor accident was followed by another, more serious crash the next day.

Furneaux said she always knew the risks associated with the sport and it was not the first time she had experienced concussion.

“With skeleton, it’s a given. You’re sliding headfirst on ice at speeds of up to 80 mph,” she said.

“It’s one of those unwritten rules that you could hit your head at any point.”

She gave evidence to the committee, pointing out a lack of awareness and understanding in sport of concussion.

She said the problem is athletes are so desperate to compete, they will say they are fine when they are not.

“You will do anything you can to compete. You might hit your head and if it’s down to you, then you will say you’re fine… as long as it’s not too bad.”

Competitors also learn how to cheat the system.

“You do head injury assessments but the more you do them, the more you start to learn them,” Furneaux added.

“You know the questions that are coming and you have to do them day in day out… I think there needs to be something like mixing up the questions so you can’t just memorise the questions.”

‘I couldn’t remember matches’

Lenny Woodard is a former professional rugby player who toured with Wales in union and represented his country in league. A few weeks ago, he was diagnosed with early onset dementia.

“It did explain the way I’d been feeling in the last five to 10 years,” he said.

“I could recall matches from when I was a child but I couldn’t remember matches I’d played in the last 10 years.

“Mid-sentence and mid-paragraph sometimes, I’d forget where I was.

“I’ve left the cooker on and burnt food and set the smoke alarms off a few times.

“I knew there was something amiss.”

During his playing days, Woodard was hospitalised for concussion a couple of times including once when he was 16 and knocked out cold.

“I fully understood and accepted the physical risks of it… I certainly didn’t envisage I’d have early onset dementia in my mid-40s.”

Woodard told 5 Live’s Adrian Chiles the responsibility for change lies with lots of people within rugby.

“There’s a culture in rugby to be the macho man, to stay on the field when you’ve been hurt. I think that needs to change,” he said,

“I think there’s a responsibility of players themselves, of parents watching their children play, not shouting things like ‘kill him’ and encouraging big violence.

“I think there’s an onus on the medical staff to overrule the player because the player will want to stay on. Especially if there’s a financial incentive.”

Woodard said he welcomed the findings of the report.

“What I want to see now is action,” he said.

‘This is the first time that it’s been acknowledged’

Monica Petrosino is a former Team GB ice hockey player who had to retire at the age of 24 after hitting her head on the ice.

She said concussion was never discussed in her early years in the sport.

“It was literally at my last World Championships in 2019 the first time there was people there that had information on concussion and were doing tests pre and post-game to track your levels,”she said.

She said she hopes the report will lead to “good outcomes”.

“This is the first time that it’s been acknowledged and acknowledgement is the first step of change,” she said.

‘We thought Bill was indestructible’

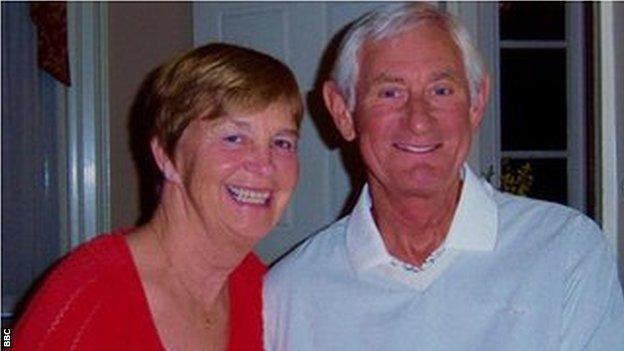

Bill Gates played football for Middlesbrough in the 1970s, and had a career spanning over 30 years.

During his career, he would head the ball dozens of times a day. In recent years he has been struggling with dementia.

His wife Judith has since helped set up the charity Head For Change, which aims to raise awareness about brain health in sport, and supports ex-players who are affected by neurodegenerative disease as a result of sports-related head injuries.

She told 5 Live’s Mobeen Azhar she was pleased that people “at the highest level” were now talking about the potential dangers of sports-related injuries but progress was still slow.

“The phrase ‘man up’ in Bill’s day would have been the cultural norm. I think it’s somewhat optimistic to think that cultural norm is significantly shifting – I think there is still a long way to go.

“One of the challenges for football is that often these outcomes that are a result of sports-related head injuries don’t manifest themselves until 20 or 30 years after playing, so then you’ve got the delayed outcomes which feed the notion that ‘nothing will really hurt me’ and the ‘man-up’ perspectives linger on.

“What I’d be saying to younger players is please take this head injury issue seriously, because we thought Bill was indestructible and we have learnt that he isn’t.”