How a New York gang truce spawned an Olympic sport

When peace broke out among New York’s gangs, breaking was born – but few foresaw it conquering the world and morphing…

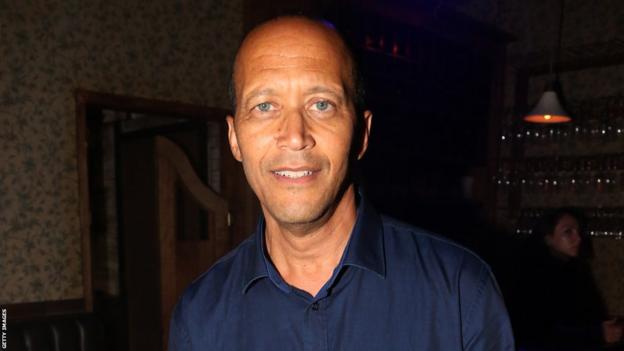

The introduction of breaking into the Olympics for Paris 2024 may have surprised many, but for Michael Holman – writer, producer, artist, entrepreneur and self-dubbed hip-hop pioneer – it was the realisation of a 40-year vision.

The Games’ website describes breaking as a “hip-hop” style of dance characterised by ‘acrobatic movement and stylized footwork’.

The format is fundamentally different to ice dancing or gymnastics though. Athletes don’t wait their turn to perform one-by-one and impress judges.

Instead breakers will take to the floor in pairs in Paris, “battling” head-to-head and upping each other’s moves to take home a medal.

Back in the early 1980s, Holman ran a weekly hip-hop revue in a downtown Manhattan club which combined rap and graffiti with the new form of street dance.

At first, it was about performance. The breakers would dance, the audience would applaud, the evening would move on and the next act would appear.

But Holman insisted on adding one more element to his booming club night.

“New York is all about competition and about trying to be the best,” he said. “And I wanted to bring another crew along to battle. I want the audience to see a battle, not just moves.”

It’s what Holman had witnessed months earlier on the streets of the Bronx. There, breaking had emerged as a form of dance combat, springing from a shift in the gang tensions that had blighted 1970s New York.

“There were the Ghetto Brothers and the Black Spades, the Savage Nomads, and the Savage Skulls. And they’d been bloodletting for years: breaking heads, killing, stabbing each other,” he said.

“Then, in 1971, Yellow Benjy – the leader of the Ghetto Brothers – forced a truce that allowed the guys and gals from rival gangs to get together and party.”

It was at these parties, where dance replaced violence as an outlet for neighbourhood bravado, that the city’s many cultures cultivated breaking’s creativity.

Holman continued: “Breakers would watch other breakers saying: ‘Wow, that’s wild. The way you’re bringing in Kung Fu moves from the Chinese community. I’m gonna incorporate your Kung Fu and put it with my African cakewalk dance, or incorporate it with a Puerto Rican gymnastics aesthetic.’ And all this while dancing to old James Brown records mixed on Jamaican-style sound systems. That’s the culture of b-boy dance.”

The first band of breakers resident at Holman’s nights were a group he informally managed called the “Rock Steady Crew”. Initially, they were loathed to share a stage with a rival outfit, but eventually they relented to Holman’s requests.

“I brought down a crew called the ‘Floor Masters’ and boom, it was like a historic moment,” said Holman. “The ‘Floor Masters’ were much more about athleticism and speed and power, and when I saw them battle, I dropped the ‘Rock Steady Crew’ like a hot potato.”

Holman helped form and then manage a new breaking crew that would focus solely on the ‘power’ moves he’d witnessed from the ‘Floor Masters’.

They recruited the best dancers from the best crews across the city’s five boroughs and named the new group the ‘New York City Breakers’. It featured some of the art form’s best exponents: Noel ‘Kid Nice’ Manguel, Matthew ‘Glide Master’ Caban, and Tony ‘Powerful Pexster’ Lopez.

Together, they took breaking to an all-new level of skill.

“I got rid of the weak dancers and raided three or four other crews from the city. I created a super crew of power breaking,” said Holman.

“The Breakers were able to like, gyroscope. They’d start out doing footwork and then go down to the ground and, using some sort of internal propulsion, mixed with the friction of the ground, simultaneously ball themselves up in a certain way or spread out in a certain way, they’d create an internal energy.

“They were able to spin and do these flares. They figured out a new way to move, and it was pure poetry.”

Holman first arrived in New York from San Francisco in 1978. Though working at a bank on Wall Street, “wearing Brookes Brothers suits each day”, he quickly fell in love with the grittier culture of the city he called home.

“I was living in a loft apartment on Hudson [Street] and Chambers [Street],” he said. “I’d get the elevator down in the morning and I’d see Joey Ramone [lead singer of iconic punk band The Ramones] – coming in from an all-night party with a girl on each arm. It was crazy.”

Holman soon became part of the scene himself, becoming friends with pioneering graffiti artist Fab Five Freddy and frequenting night spots like Max’s Kansas City, Mudd Club and CBGBs; venues that allowed him to mix with musicians, poets and other up-and-coming artists.

“I was eating-in New York like ice cream,” Holman said, wistfully, recalling that he was on his way back from a late-night party of his own when he saw the first signs of a new street culture emerging around him.

“I was half asleep waiting for a subway. And then this train comes into the station and it’s covered, top-to-bottom, across all the windows with graffiti logos and burners [large, elaborate designs in spray paint]. And I’d never seen anything like it before, it was an insane message from the street. It was vandalism, but beautiful at the same time.

“Young kids saying: ‘Look at me. Look what I can do. I’m not a nobody. OK, so this city houses the United Nations, it’s the capital of media and finance but I’m a kid from the Bronx, and I’ve got game, too!'”

For Holman, this ethos was also behind hip-hop’s emergence and breakers’ compulsion to express themselves through dance.

“It’s about, look at me, I’m somebody,” he said. “I can take a microphone and write my own poetry, I can cut and scratch a turntable, I can rock the floor like a b-boy, I can pull off head spins like you can’t even imagine.

“Kids were creating their own universe with nothing more than two turntables, a mic and a piece of linoleum.”

As Holman made music, shot films and soaked up New York’s energy, he wondered if the city’s small hip-hop and breaking scene could become a break-out trend, just like punk which had sprung up in London and New York in the previous decade.

“A friend of mine went to school with Malcolm McLaren back in the 1960s,” said Holman.

“When McLaren visited New York, I invited him to a block party in the Bronx with Afrika Bambaataa and Jazzy Jay. I took him to a park jam, where the DJs had their sound systems and where the b-boys and b-girls went to dance.

“Malcolm was blown away and so he asks me to put together a review. Well, I did that.”

McLaren had a good instinct for revolutionary cultural movements. He had managed the Sex Pistols, who became punk figureheads after releasing their anti-monarchist single ‘God Save the Queen’ to coincide with Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977.

He connected Holman with an English-born promoter in the city called Ruza ‘Kool Lady’ Blue who had a regular night at the Jamaican-owned NeGril nightclub.

And by November 1981, the nightspot was rocking to Holman’s DJ friends and the The Rock Steady Crew breakers.

Once word got around about the hip-hop nights, a newly-formed super-troupe and their amazing displays of breaking on show at Holman’s NeGril nights, the New York media started to take notice too.

“Well, what we were doing became the flavour of the month for these international broadcast companies,” he said. “You’ve got documentary crews from all over the world in New York: the BBC, Canal Plus, NHK, Rai TV and ZDF.

“They go film the Breakers, package it up and send it back to wherever they’re from. And it goes on the news that night. So you got kids in London and Tokyo and Paris exposed to hip-hop culture before even the kids in Pittsburgh were.”

Holman decided to make some content of his own. He created and presented the TV show Graffiti Rock in 1984, a hip-hop-dedicated music show along the lines of the successful Soul Train, which featured Run-DMC, Kool Moe Dee and Special K, along with the New York City Breakers.

“It was the first hip-hop TV show in the world,” said Holman.

The New York City Breakers also crossed over into Middle America’s mainstream. They appeared on the Merv Griffin Show – a popular American talk show – the CBS Evening News, Good Morning America and Soul Train itself. They featured in a music video, pulling moves while soul legend Gladys Knight sang Save the Overtime (For Me).

The last major event Holman booked for the New York City Breakers was at the London Contemporary Dance Trust in 1987.

“By then the gigs were dying out. It was seen as a passing fad. The media had moved on and the breakers were starting to go their different ways,” he said.

But elsewhere, the party went on.

“As with a lot of cultural movements that start in America, like jazz, rock ‘n’ roll and blues; they die out here only to find a new life and a new identity overseas. Same happened with breaking,” Holman added.

By the late 1990s, Holman was getting invites to hip-hop conventions all over the world, with interest in Australia, Asia, Europe and South America.

He hosted panels and lectures about the breaking movement, watched breaking films and took part in dance workshops where the original dancers had been asked to make an appearance.

One young Polish dance crew even made a point of showing him they’d learned a routine from Graffiti Rock, move for move. But not all breakers were as welcoming.

“I used to get a lot of screwy looks from some of the breakers when I showed up,” said Holman.

“They would say: ‘Oh, you’re the one trying to push this as a sport, trying to kill the art form.’

“But I always felt the movement had a mind and life of its own. The culture itself is sentient. Hip-hop is now collectively a multi-billion dollar industry that’s impacted the world.

“There were the same debates about skateboarding and extreme sports. There was outcry at the thought of an art form being ‘judged’, with points and scoring. I’m sure figure skating was the same in the 1930s.

“But just consider the fact that this is a movement created in New York City; the capital of commerce, the belly of the capitalism beast. To question its path toward competition and commercialisation is naive at best.”

Debate aside, breaking’s remarkable battle the from Bronx’s sidewalks to the Olympic stage is gratifying for Holman, one of the few who grasped the potential of its power-moves and poetry more than four decades ago.