The secret tapes of Jamal Khashoggi’s murder

The audio tapes that recorded the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. …

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Warning: Graphic content

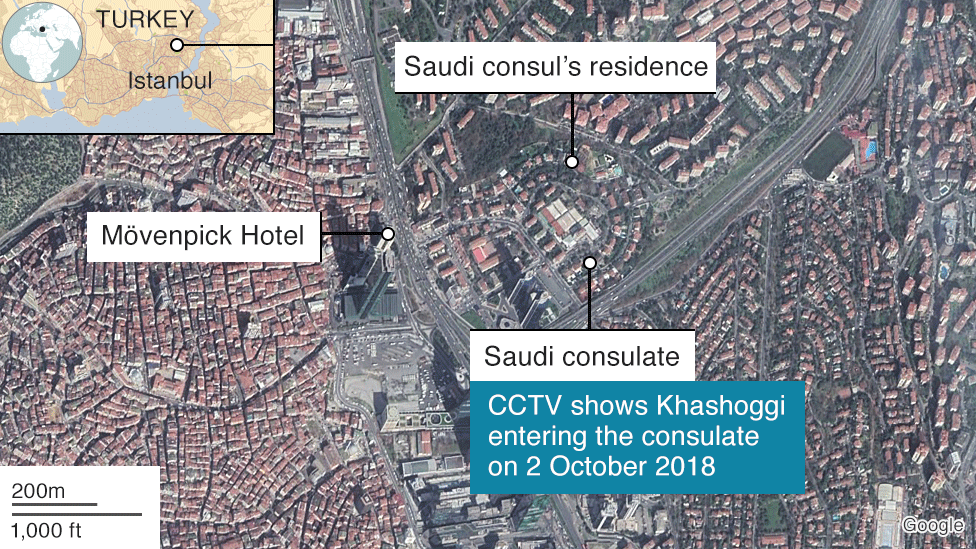

I walked along a tree-lined street in a quiet area of Istanbul and approached a cream-coloured villa, decked with CCTV cameras.

A year ago, an exiled Saudi journalist took the same journey. Jamal Khashoggi was caught on CCTV. It would be the last image of him.

He entered the Saudi consulate and was murdered by an assassination squad.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters

But the consulate was bugged by Turkish intelligence – the planning and the execution were all recorded. The tapes have only been heard by very few people. Two of those people have now spoken exclusively to the BBC’s Panorama programme.

British barrister Baroness Helena Kennedy listened to Jamal Khashoggi’s dying moments.

“The horror of listening to somebody’s voice, the fear in someone’s voice, and that you’re listening to something live. It makes a shiver go through your body.”

Kennedy made detailed notes of the conversations she heard between members of the Saudi hit squad.

“You can hear them laughing. It’s a chilling business. They’re waiting there knowing that this man is going to come in and he’s going to be murdered and cut up.”

Kennedy was invited to join a team headed by Agnès Callamard, the UN’s special rapporteur for extrajudicial killing.

Callamard, a human rights expert, told me of her determination to use her own mandate to probe the killing, when the UN proved reluctant to mount an international criminal investigation.

It took her a week to persuade Turkish intelligence to let her and Kennedy, along with their Arabic translator, listen to the tapes.

“The intention clearly on the part of Turkey to give me access, was to help me prove planning and premeditation,” she says.

They were able to listen to 45 minutes, extracted from recordings made on two crucial days.

Jamal Khashoggi had been in Istanbul – a city where opponents of regimes across the Middle East have long sought refuge – for a few weeks before he was killed.

The 59-year-old divorced father of four had recently become engaged to Hatice Cengiz, a Turkish academic researcher.

They were hoping to build their life together in this cosmopolitan city, but to remarry, Khashoggi needed his divorce papers.

On 28 September, he and Cengiz visited the Turkish municipal office but were told they needed to get the papers from the Saudi consulate.

“This was the last resort. He had to go and get those documents from the consulate for us to get officially married because he couldn’t go back to his country,” Cengiz tells me when I meet her in a cafe.

Khashoggi hadn’t always been an outcast, exiled from his own country. I met him 15 years ago at the Saudi embassy in London’s Mayfair. He was then at the heart of the Saudi establishment – a smooth-talking aide to the ambassador.

We discussed a recent terror attack by al-Qaeda. Khashoggi had known its Saudi leader, Osama bin Laden, for decades. Initially Khashoggi had some sympathy for al-Qaeda’s aim to overthrow autocratic Middle Eastern regimes. But later, he spoke out against the group’s atrocities as his views became more liberal and he championed democracy.

In 2007, he returned home to edit the pro-government newspaper al-Watan. But he was fired three years later for what he described as “pushing the boundaries of debate within Saudi society”.

By 2011, inspired by the events of the Arab Spring, Khashoggi was speaking out against what he saw as the repressive and autocratic Saudi regime. By 2017 he had been banned from writing and went into self-imposed exile in America. His wife was forced to divorce him.

Khashoggi became a contributor for the Washington Post, for whom he wrote 20 hard-hitting columns in the year before he died.

“When he was an editor in the Kingdom he would cross red lines,” says his friend David Ignatius, the Post’s senior foreign affairs columnist and investigative journalist. “What I saw with Jamal was that he kept getting himself in trouble by speaking his mind.”

Much of Khashoggi’s criticism was targeted at the new crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman.

MBS, as he is known, was admired by many in the West. He was seen as a reformer and moderniser with a new vision for his country.

But at home in Saudi Arabia, he was cracking down on dissent and Khashoggi was highlighting it in the pages of the Post.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters

This was not the image the crown prince wanted to project.

“I think that particularly aggravated the crown prince, and he kept asking his aides to do something about this Jamal problem,” says Ignatius, who regularly visits Saudi and writes about its politics.

In Istanbul, the Saudis were presented with an opportunity to “do something” about Khashoggi.

On the day of his first visit to the consulate, Cengiz had to remain outside.

She remembers Khashoggi coming out of the building with a smile on his face. He told her that officials had been surprised to see him and had offered him tea and coffee.

“He said there was nothing to be afraid of, he missed his country so much and breathing that familiar air had made him feel really good.”

Khashoggi was told to come back in a few days.

But as soon as he was gone, phone calls were being made back to Riyadh in Saudi Arabia – all recorded by Turkish intelligence.

“What was interesting about this phone call is that it referred to Mr Khashoggi as one of the persons that was being sought,” says Callamard.

The first call is believed to have alerted the powerful aide who ran MBS’s so-called communications office – Saud al-Qahtani.

“Someone in the communication office had authorised the mission. It makes sense to see that reference to the communication office as being a reference to Saud al-Qahtani,” she continues.

“He has been named directly in various other campaigns against individuals.”

Image copyright Twitter

Image copyright Twitter

Al-Qahtani had already been accused of involvement in the detention and torture of dissidents in Saudi, such as female activists who dared to drive before the ban was lifted, and high-profile individuals suspected of disloyalty.

In his writings, Khashoggi had accused al-Qahtani of operating a “blacklist” for the crown prince.

“Qahtani began doing extraordinary services – secret black operations,” says Ignatius, who has investigated the royal aide. “That became part of his portfolio and he managed it with a particular ruthlessness.”

There are recordings of at least four phone calls on 28 September between the consulate and Riyadh. These include conversations between the consul general and the head of security at the ministry of foreign affairs, who told him a top-secret mission – “a national duty” – was planned.

There’s no doubt in my mind this was a seriously, highly organised mission coming from the top,” says Kennedy.

“This was not some flaky, maverick operation on the side.”

On the afternoon of 1 October, three Saudi intelligence officers flew into Istanbul. It’s known that two worked in the office of the crown prince.

Callamard believes they were on a reconnaissance mission.

“They probably assess the consulate building, they determine what can and cannot be done.”

On a quiet and shady terrace in Istanbul, overlooking the Bosphorus, I meet a former Turkish intelligence officer with 27 years’ experience.

Metin Ersöz is an expert on Saudi Arabia and its special operations missions. He says its intelligence services became more aggressive after Mohammed bin Salman became crown prince.

“They started the kidnapping operations and pressuring dissidents,” he says.

“Khashoggi was late in recognising the threat and taking precautions and he would pay a heavy price for it.”

In the early hours of 2 October, a private jet landed at Istanbul airport.

On board were nine Saudis – including a forensic pathologist named Dr Salah al-Tubaigy.

After probing their identities and backgrounds, Callamard believes this was the Saudi hit squad.

“The operation was conducted by state officials, they were acting in their official capacities,” she says.

“Two of them had diplomatic passports.”

Ersöz says that this kind of mission – a special operation – would have needed approval from either the Saudi King or the crown prince.

The Saudis checked into the large and impersonal Mövenpick Hotel, located within a few minutes’ walk of the consulate.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters

Just before 10:00, CCTV shows one of the hit squad entering the Saudi consulate.

From listening to the tapes, Kennedy believes that Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb was the man who ran the operation.

Mutreb was regularly seen travelling with the crown prince, discreetly in the background, close to him as part of his security detail.

“In the calls between the consul general and Mutreb, there’s a reference to the fact that ‘we received the information Khashoggi will be coming on Tuesday’,” says Kennedy.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

Later on the morning of 2 October, Khashoggi received a call to come to the consulate for his documents.

As he and Cengiz walked towards the consulate, a macabre and shocking phone conversation was taking place inside between Mutreb and the forensic pathologist, Dr al-Tubaigy.

“He talks about how when he’s doing autopsies. You can hear them laughing,” Kennedy says.

“He says, ‘I often play music when I’m cutting cadavers. And sometimes I have a coffee and a cigar at hand.'”

Then the tapes reveal the doctor knows what he is expected to do, according to Kennedy.

“It’s the first time in my life, I will have to cut (up) pieces on the ground,” she recalls him saying. “Even if you are a butcher you hang the animal up to do so.”

An upstairs office in the consulate had been made ready. The floor was covered in plastic sheeting. Local Turkish staff had all been given the day off.

“They speak about… when is Khashoggi to arrive, and they say, ‘Has the sacrificial animal arrived?’ That’s how they refer to him,” says Kennedy.

She is reading to me from her notebook, horror in her voice.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters

At 13:15, CCTV shows Khashoggi entering the consulate building.

“I remember we walked there hand-in-hand and when we arrived in front of the consulate, Jamal gave me his phones and said, ‘See you later darling, wait for me here,'” says Cengiz.

Khashoggi knew his phones would be taken at the entrance and did not want the Saudis to access his private information.

The tapes reveal that he is met by a reception committee and told that there is an Interpol warrant out for his arrest and he must return to Saudi Arabia.

He is heard refusing to text his son to assure the family he is fine.

The silencing of Jamal Khashoggi then begins.

Watch The Khashoggi Murder Tapes on Monday 30 September at 20:30 on BBC One (Wales 22:35). Or on BBC iPlayer

“There was a point where you can hear Khashoggi moving from being a man who’s a confident person, towards a sense of fear – rising anxiety, rising terror – and then knowing that something fatal is about to happen,” says Kennedy.

She continues: “There’s something absolutely horrifying about the voice changing. The cruelty of it comes across by listening to the tapes.”

Callamard is not sure how aware Khashoggi was of the Saudis’ plans: “I don’t know whether he thinks he could be killed, but he certainly thinks that they could try to abduct him. He is asking, ‘Are you going to give me an injection?’ to which he’s being told ‘Yes’.”

Kennedy says she heard Khashoggi asking twice whether he is being kidnapped and then saying, ‘How could this happen in an embassy?'”

“The sounds that are heard after that point will tend to indicate that he’s suffocated. Probably with a plastic bag over his head,” says Callamard. “His mouth was also closed – violently – maybe with a hand or something else.”

Kennedy believes the forensic pathologist now takes over on the orders of the team leader.

“You hear a voice saying, ‘Let him cut,’ and it sounds like Mutreb.

“Then somebody shouting, ‘It’s over,’ and someone else shouting, ‘Take it off, take it off. Put this on his head. Wrap it.’ I can only assume that they had removed his head.”

For Cengiz, only half an hour had passed since Khashoggi left her outside the consulate.

“During that time, I was dreaming of my future – like how our wedding would be. We were planning a small ceremony,” she says.

About 15:00, CCTV shows consular vehicles leaving and arriving at the consul general’s residence two streets away.

Three men enter with suitcases and plastic bags. Callamard believes they may have contained parts of the body.

A car later drives away. Khashoggi’s body has never been found.

What about the most disturbing detail reported at the time of the murder – the bone saw used to dismember the body?

Kennedy says she did not hear the kind of grating noise she would have associated with that type of surgical instrument on the tape. But she says there was a low-level humming sound. Turkish intelligence officials believe this was the sound of the saw.

At 15.53, CCTV shows two members of the hit squad leaving the consulate.

I retraced their footsteps down the street past the cameras that detailed their route between the consulate and the heart of old Istanbul.

One man is dressed in Khashoggi’s clothes, but wearing different shoes. The other man, his face obscured by a hoodie, is carrying a white plastic bag.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters

They head towards Istanbul’s famous Blue Mosque. When they re-emerge, the man previously dressed in Khashoggi’s clothes has changed.

They hail a taxi back to their hotel, dumping the plastic bag – thought to contain Khashoggi’s clothes – in a bin nearby, before going down into a subway and back to the Mövenpick Hotel.

“There was a very large degree of planning used to give the impression that nothing harmful had happened to Mr Khashoggi,” says Callamard.

All this time, Cengiz was still waiting outside the consulate.

“I waited and waited and waited there past 15:30. Then, when I realised the consulate had closed, I started running towards it. I asked why Jamal didn’t come out. A guard told me he didn’t know what I was talking about.”

At 16:41, Cengiz was desperate and phoned an old friend of Khashoggi’s. He had given her the number in case he was ever in trouble.

Dr Yasin Aktay is a member of Turkey’s ruling party with contacts at the highest levels.

“I received a call from an unknown number, a really worried voice from a lady I didn’t know,” he says. “She said, ‘My fiance Jamal Khashoggi went into the Saudi consulate and didn’t come out.'”

Yasin swiftly called the head of Turkish intelligence and alerted the office of President Tayyip Erdogan.

By 18:30, the members of the hit squad were on a private jet to Ryiadh, less than 24 hours after they had arrived.

The next day, the Saudi and Turkish governments issued contradictory statements about what had happened inside the consulate. Saudi Arabia insisted Khashoggi had left the consulate. The Turks said he was still inside.

Turkish intelligence was already poring over the consulate recordings – including the calls made four days before Khashoggi disappeared.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

So did they know at that time that his life was in danger and, if so, why did they not warn him?

“I don’t think they knew. There is no evidence that they were listening live to what was happening,” says Callamard.

“This kind of intelligence is done on a regular basis, and it’s only because there is a trigger that they may return to the tapes. It was only because Mr Khashoggi was killed and disappeared that they returned to the tape.”

Ersöz tells me his former intelligence colleagues reviewed the tapes retrospectively and went through between 4,000 and 5,000 hours of material to find the key days and the 45 minutes presented to Callamard and Kennedy.

Four days after Khashoggi was killed, another Saudi team arrived – claiming they had come to find out what had happened.

Callamard believes they were really a clean-up team. The consulate is sovereign Saudi territory under international law, and for two weeks the Saudis would not allow Turkish investigators to enter.

“By the time they were able to collect some evidence, there was nothing there, not even DNA evidence of Mr Khashoggi having been there,” says Callamard.

“The only logical conclusion is that the place was thoroughly, forensically cleaned.”

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

That evening, the Turkish authorities told the media that Khashoggi had been murdered in the Saudi consulate.

“Jamal really didn’t deserve this, He deserved so much better,” says Cengiz. “The way they killed him, it killed all my hope in life.”

The killing in Istanbul, inside an embassy with diplomatic immunity, put the Turkish authorities in a quandary.

For weeks, despite mounting pressure from the Turks, the Saudis refused to admit the murder, saying first there had been “a fist fight” in the consulate and then claiming it was “a rogue operation”.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

The Turkish authorities’ strategy was to leak some of what they knew to local and international press. They then invited representatives from the CIA and a few handpicked intelligence agencies, including MI6, to listen to the tapes, proving Khashoggi was murdered by Saudi state operatives.

The CIA reportedly came to the conclusion there was “medium to high certainty” that Mohammad bin Salman had ordered the killing. They briefed Congressmen who were left in no doubt about the finding.

In January, the Saudi government finally put 11 people on trial in Riyadh for the murder of Khashoggi, including Mutreb and Dr al-Tubaigy, but not the alleged mastermind – Saud al-Qahtani.

He has not been indicted or even summoned to court to give evidence. I have been told he is being kept in seclusion away from everyone, including his own family, but is still in contact with the crown prince.

Callamard’s report for the UN Human Rights Council has reached a decisive conclusion.

“There is no indication under international law that this crime could be qualified under any other way but as a state killing,” she says.

Kennedy says the revelations of the Khashoggi murder tapes must be acted on.

“Something treacherous and terrible happened in that embassy. The international community has a responsibility to insist on a high-level judicial enquiry,” she says.

Turkey has demanded the extradition of those involved to face trial in Istanbul. But Saudi Arabia has refused.

The Saudi government declined to give an interview to Panorama, but said it condemned the “abhorrent killing” and it was committed to holding the perpetrators accountable.

It said that the crown prince had “absolutely nothing to do” with what it called a “heinous crime”.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters

One year on, as we leave the cafe, I can see the pain still suffered by the woman left behind when her fiance’s life was cut short so brutally.

In her parting words to me, Hatice Cengiz warns of the true significance of the killing of Jamal Khashoggi.

“It’s not only a tragedy for me – but for all humanity, all the people who think like Jamal and who took a stance like him.”

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

All images subject to copyright