Is being labelled a hippy a form of insult?

The Duke of Sussex says calls to protect nature should not be dismissed as “hippy”. …

The Duke of Sussex has warned that humanity must “overcome greed” in order to save itself and the natural world.

Prince Harry told Daily Telegraph readers that his rallying call “may sound a bit hippy”.

But does being labelled a hippy actually conjure up negative connotations – and why would it be used to dismiss his rallying call?

What does the word ‘hippy’ mean?

Amid the rise of jazz culture in the US of the 1930s, the term “hip” was used as something desirable.

“You wanted to be a hipster then,” says slang expert Jonathan Green.

However, by the 1950s the word “hippy” arrived – with a far less positive image.

“The word was used to mock someone who wasn’t really hip and to describe someone who was lacking hipness,” says Green.

Use of the word continued to evolve over time and by the 1960s it would have a meaning closer to today’s.

In 1967 celebrated American novelist Hunter S Thompson described hippies as “very hairy people, full of flower power”.

Two years later, in London, underground-culture fanzine Gandalf’s Garden had a go. It defined hippy (n) as: “a fabrication of the straight press to denote ordinary people with longish hair, beards and colourful clothes”.

So who is a hippy then?

For many, when they think of hippies they may well think of radical politics, free love and, to quote singer Scott McKenzie, wearing “flowers in your hair.”

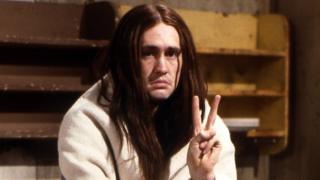

Some will picture Woodstock music festival, other will think of Neil from 1980s TV programme The Young Ones, and for some it may be the South Park episode which sees Cartman try to clear the town of “spaced-out” hippies in headbands and tie-dye tops.

So is this imagery a fair reflection?

Fashion historian Casci Ritchie says individuality and self-expression were at the centre of early hippy subculture.

Long fringes and beading, handmade textiles such as macramé and crochet were central to the look.

“Second hand and army surplus stores also offered young people affordable, alternative clothing to that of the mainstream.

“With many people travelling across the globe, there was an apparent appropriation of different cultures, with traditional garments such as ponchos, dashikis and tunics worn alongside Westernised blue ‘hip-hugger’ jeans,” she says.

For former hippy, and current language expert, Tony Thorne, being a hippy was much more than getting the look.

“The hippy ideals of peace and love – which were genuine, I was one – were mocked from the start by straight bourgeois society and by politicians and much of the conservative media.”

He adds that those using the term in the 1960s and 1970s generally meant it as a “slur”.

“Hippies never referred to themselves by the name but as ‘freaks’ or as members of the alternative society.”

Do today’s activists try to avoid the tag?

Earlier this month, millions around the world took to the streets to call for action to tackle climate change.

In April thousands joined protests in London organised by campaign group Extinction Rebellion.

“There’s nothing wrong with being a hippy,” says the group’s strategist Ronan Harrington.

“But we’re aware that it presents difficulties for the mainstream.

“They can see it as secular and dangerous or that it’s an affront to mainstream values like hard work, getting your head down and becoming a success.”

He says that the term has become a “tired trope” used by critics.

And, as in the case of some recent criticism of teenage activist Greta Thunberg, he says using the term “hippy” can be used as a way to “dismiss the person rather than looking at their concerns or beliefs.”

Extinction Rebellion is planning more protests in London next month. And Mr Harrington says the demonstrations will include “groups that maybe break the stereotype of the conventional activist”.

“You’ll see tractors in Westminster with farmers telling how this climate and ecological emergency is affecting them.

“There will be doctors in Whitehall who will be there to tell people about the great health risks we’re facing.”

He adds: “I think that maybe people are seeing beyond that and saying ‘hang on a second how does this affect me – are my children going to be okay?'”

How are hippies seen today?

Hippy style might no longer be seen as part of the counterculture, but as fashion expert Ms Ritchie suggests, we may have come full circle.

She cites global movements such as Fashion Revolution’s “Who Made My Clothes” and MPs calling for an end to throwaway fast fashion.

“We are becoming more accountable for the impact our fashion has on our environment, she says.

“Shopping second hand is not just seen as a fashionable place to buy unusual clothing – it is now being recognised as a way to combat against the fast fashion industry.”

However, while the culture may have been usurped – as Prince Harry demonstrated – the word has not.

Slang expert Mr Green, adds: “The young will make fun, perhaps correctly, at the older generations but it’s interesting how the word hippy has hung around to be pillared today.”

“Perhaps, Neil from the Young Ones sums it up best. We loved him – but no one wanted to be him”.