And ‘Lo!’ – How the internet was born

Interface Message Processors built the Arpanet, which led to the internet of today. …

In the 1960s, Bob Taylor worked at the heart of the Pentagon in Washington DC. He was on the third floor, near the US defence secretary and the boss of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (Arpa).

Arpa had been founded early in 1958 but was quickly eclipsed by Nasa, leading Aviation Week magazine to dismiss it as “a dead cat hanging in the fruit closet”.

Nevertheless, Arpa muddled on – and in 1966, Taylor and Arpa were about to plant the seed of something big.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme’s sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Next to his office was the terminal room, a pokey little space where three remote-access terminals with three different keyboards sat side by side.

Each allowed Taylor to issue commands to a far-away mainframe computer.

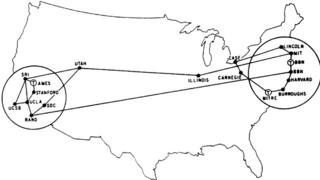

One was based at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), more than 700km (450 miles) up the coast.

The other two were on the other side of the country – one at the University of California and the Strategic Air Command mainframe in Santa Monica, called the AN/FSQ32XD1A, or Q32 for short.

Each of these massive computers required a different login procedure and programming language.

It was, as the historians Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon put it, like “having a den cluttered with several television sets, each dedicated to a different channel”.

Although Taylor could access these computers remotely through his terminals, they could not easily connect to each other – nor could other Arpa-funded computers across the United States.

Image copyright Gardner Campbell/Wikipedia

Image copyright Gardner Campbell/Wikipedia Sharing data, dividing up a complex calculation or even sending a message between these computers was all but impossible.

The next step was obvious, Taylor said. “We ought to find a way to connect all these different machines.”

Taylor talked to Arpa’s boss, Charles Herzfeld, about his goal.

“We already know how to do it,” he said, although it was not clear that anyone really did know how to connect together a nationwide network of mainframe computers.

“Great idea,” said Herzfeld. “Get it going. You’ve got $1m more in your budget right now. Go.”

The meeting had taken 20 minutes.

MIT’s Larry Roberts had already managed to get one of his mainframes to share data with the Q-32 – two supercomputers chatting on the phone.

It had been slow, fragile, and fussy to make it work.

But Taylor, Roberts and their fellow networking visionaries had something much more ambitious in mind – a network to which any computer could connect.

As Roberts put it at the time, “almost every conceivable item of computer hardware and software will be in the network”.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images That was an enormous opportunity – it was also a formidable challenge.

Computers were rare, expensive, and puny by modern standards.

They were typically programmed by hand by the researchers who used them.

Who would persuade these privileged few to set aside their projects to write code in the service of someone else’s data sharing project?

It was like asking a Ferrari owner to idle the engine in order to heat up a fillet steak, before feeding it to someone else’s dog.

The solution was proposed by another computing pioneer, physicist Wesley Clark.

Clark had been following the emergence of a new breed of computer.

The minicomputer was modest and inexpensive compared with the room-sized mainframes installed in universities across the United States.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Clark suggested installing a minicomputer at every site on this new network.

The local mainframe – the hulking Q-32, for example – would talk to the minicomputer sitting close beside it.

The minicomputer would then take responsibility for talking to all the other minicomputers on the network – and for the new-and-interesting problem of moving packets of data reliably around the network until they reached their destination.

All the minicomputers would run in the same way – and if you wrote a networking program for one of them, it would work on them all.

More things that made the modern economy:

Adam Smith, the father of economics, would have been proud of the way Clark was taking advantage of specialisation and the division of labour – perhaps his defining idea.

The existing mainframes would keep on doing what they already did well.

The new minicomputers would be optimised to reliably handle the networking without breaking down.

And it surely wouldn’t hurt that Arpa could simply pay for them all.

In one episode of the television comedy series The IT Crowd, the geek heroes convince their technologically clueless boss, Jen, they have “the Internet” – a small box with a winking light.

They offer to lend it to her as long as she promises not to break it.

The beauty of Clark’s idea was that, as far as any particular computer was concerned, this was pretty much how the network would appear.

Each local mainframe had to be programmed merely to talk to the little black box beside it – the local minicomputer.

If you could do that, you could talk to the entire network that stood behind it.

The little black boxes were actually large and battleship grey.

They were called Interface Message Processors (IMPs).

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images The IMPs were customised versions of Honeywell minicomputers, which were the size of refrigerators and weighed more than 400kg (63 stone) apiece.

They cost $80,000 each, more than $500,000 (£405,000) in today’s money.

The network designers wanted message processors that would sit quietly, with minimal supervision, and just keep on working, come heat or cold, vibration or power surge, mildew, mice, or – most dangerous of all – curious graduate students with screwdrivers.

Military-grade Honeywell computers seemed like the ideal starting point, although their armour plating may have been overkill.

The prototype, IMP 0, emerged early in 1969. It did not work.

A young engineer worked on fixing it for months, manually unwrapping and rewrapping wires on pins about 1mm apart.

It wasn’t until October that year that IMP 1 and IMP 2 were in position at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Stanford Research Institute, more than 500km up the coast.

On 29 October 1969, two mainframe computers exchanged their first word through their companion IMPs.

It was, somewhat biblically: “Lo”.

The operator had been trying to type: “Login” and the network had collapsed after two letters.

A stuttering start – but the Arpanet had been switched on.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Other networks followed, as did a decade-long project to interconnect these into a network of networks – or simply, “the internet”.

Eventually, the IMPs were supplanted by more modern devices called routers. By the late 1980s, they were museum pieces.

But the world Roberts had predicted, in which “almost every conceivable item of computer hardware and software will be in the network”, was becoming a reality.

And the IMPs had shown the way.

The author writes the Financial Times’s Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme’s sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.