Top psychologist: No certainty terror offenders can be ‘cured’

A top psychologist says there is probably no scheme that can “cure” or “de-programme” a terror offender. …

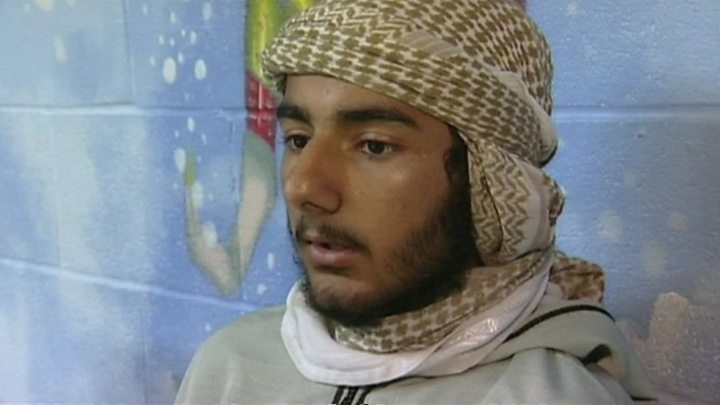

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images The psychologist behind the UK’s main deradicalisation programme for terror offenders says it can never be certain that attackers have been “cured”.

Christopher Dean told the BBC some terror offenders who take part in his Healthy Identity Intervention (HII) scheme appear to regress because of their uniquely complex identities.

Mr Dean spoke out after HII participant Usman Khan stabbed two people to death near London Bridge on 29 November.

Khan, 28, was shot dead by police.

He was jailed eight years ago for planning to set up a terrorism training camp – but appeared to be responding to rehabilitation by the time of his release in December 2018.

In the attack in November he killed Jack Merritt, 25, and Saskia Jones, 23, at a prisoner rehabilitation event in Fishmongers’ Hall in the City of London.

The HII scheme involves the offender attending repeated sessions with a psychologist who encourages them to talk about their motivations, beliefs, identity and relationships with both other extremists and the rest of society.

The aim, forensic psychologist Mr Dean said, is to find ways to get the offender to think deeply about what they really want from life – and this can lead them to voluntarily abandoning extremism and violence.

Speaking to BBC Radio Four’s Today programme in his first broadcast interview, Mr Dean said the work was complex because the offenders were different to almost all others in jail.

“The two main aims of healthy identity intervention are primarily to try and make individuals less willing or prepared to commit offenses on behalf of a violent extremist group cause or ideology,” he said.

“If we can reduce someone’s relationship or identification with a particular group, cause or ideology, that in itself may have an impact on whether they’re willing to offend or not.”

Mr Dean said some complex offenders he had worked with needed 20 or more sessions to show signs of positive change, because of the depth of their indoctrination.

“We see some individuals who may have been part of a group for many years or have been invested or identified with the cause for many years. [Leaving that group] is an incredibly difficult thing to do,” he said.

“Sometimes offenders will sit opposite you and say, ‘So you’re here to de-programme me?’

“It’s almost like a robotic term in that we’re going to simply download everything in your head, and we’re going to pump it full of something else. And I don’t think that’s what we’re doing,” he added.

“We’re asking people to kind of reconsider or re-examine the identity commitments in their life… why they may have bought into a particular cause and support in violence on behalf of that cause.

“This is something you can’t force people to do. It isn’t about telling someone you have to be this way, or this is how you have to be. Human behaviour doesn’t work like that.”

The inquests into the deaths of Khan’s victims are likely to hear evidence about how the killer was managed in prison and in the community after his release.

Mr Dean told the BBC the HII sessions were only one part of attempts to manage such offenders – and the results of the prison scheme should be clearly understood by the probation and police officers monitoring someone after their release.

“Sometimes people move up two rungs. Sometimes individuals may say… I’ve had my doubts… but equally, they may go down rungs as well,” he said.

“They may come into contact with individuals or they may go through a spell in life where they may begin to re-engage with groups or causes or ideologies associated with their offending behaviour.

“I think we have to be very careful about ever saying that somebody no longer presents a risk of committing an offence. I don’t think you can ever be sure. We have to be very careful about saying someone has totally changed or has been cured.”

The Ministry of Justice has not completed any work to test whether the HII scheme prevents reoffending or successfully tackles extremist behaviour – and there has been no similar exercise to test the effectiveness of the follow-on programme Khan joined after his release on licence.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

However, Mr Dean said that when he and colleagues devised HII it was not rolled out until an external panel of experts assessed whether it was clearly based on the best-available evidence about challenging extremist mindsets.

HII could not currently be tested like other rehabilitation programmes, he said, because there were too few offenders to get a scientifically-robust assessment of what worked.

Mr Dean said it would also be unethical to exclude some offenders from the scheme because of the risk of them returning to terrorism when there had been an opportunity to intervene in their lives while in prison.

“I think we need to be careful about suggesting that interventions in themselves are the solution,” he added.