UK’s Halley Antarctic base in third winter shutdown

Image copyright LANDSAT/USGS/NASA

Image copyright LANDSAT/USGS/NASA

The British Antarctic Survey has closed its Halley base for another winter.

Staff departed the station, leaving about 80% of the experiments they’d normally conduct through the polar night operating on automatic.

The closure is the result of the ongoing uncertainty surrounding the stability of ice near Halley that is likely soon to break off into the sea.

BAS believes the base is far enough away to be unaffected, but it doesn’t want people there just in case.

Sending in planes to evacuate personnel in winter darkness and in bad weather is an unnecessary risk.

This is the third winter on the trot now that Halley has been closed up.

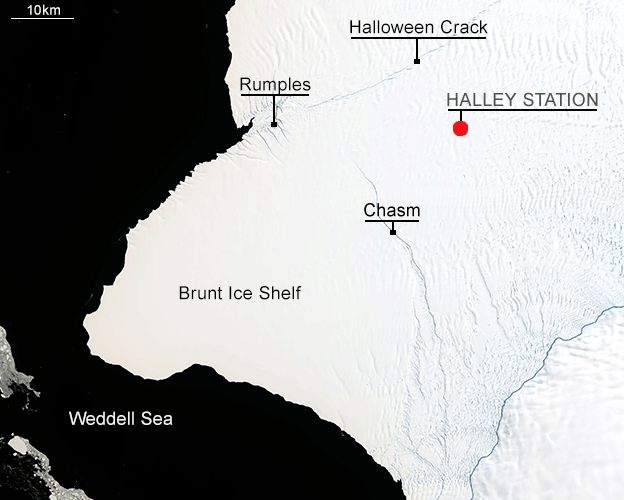

The base sits on the Brunt Ice Shelf – the floating protrusion of glaciers that are flowing off the Antarctic interior into the Weddell Sea.

Periodically, this platform will calve icebergs and there is presently a large chasm opening up that will spawn a particularly big block – about the size of Greater London.

But when precisely this will occur, no-one can say.

“What really matters is what happens upstream of the chasm where Halley is situated,” explained BAS science director Prof David Vaughan.

“We have a network of about 15 GPS stations across the ice shelf surrounding Halley, and their data is essentially broadcast to us every day with one day’s lag. And although, yes, down by the crack, there are changes – up by Halley, we’ve actually seen very little deformation of the ice,” he told BBC News.

There’s been a permanent research station on the Brunt since the late 1950s. The buildings have gone through various upgrades with the most recent facility featuring legs and skis. These enable the whole segmented structure to be moved.

In 2017, BAS tractors dragged the base 23km further from the water’s edge, to put it in a more secure spot. It was a smart decision because without the relocation Halley would now be sitting on the wrong side of the chasm.

Glaciologists continue to use satellite images of the region to monitor the behaviour of the chasm. The situation has been complicated somewhat by the emergence of an additional fissure, dubbed the Halloween Crack, which runs off in a different direction.

How events play out will depend in large part on what happens in an area of shallow water known as the McDonald Ice Rumples.

This bump on the bottom of the Weddell Sea acts as pinning point that holds back and stabilises the 150m-thick Brunt shelf. Just where the chasm breaks through to the rumples – and it has about 4.5km to go – will almost certainly influence the reaction of upstream ice.

Halley is enormously important to BAS activities.

As well as acting as the launch pad for forays into the Antarctic deep field, it gathers essential weather and climate data.

Famously, it played a critical role in the research that identified the ozone “hole” in 1985, and in recent years has also become a major centre for studying solar activity and the impacts this has on Earth.

Survey staff have been working hard to try to maintain observations even though they themselves will not be present.

A key fix is the installation of a micro-turbine – a kind of “jet engine in a box”. This is providing the power for automated instrumentation, including the Dobson photospectrometer that keeps an eye on the ozone layer.

Running experiments in the Antarctic without people is a challenge because of the harsh conditions.

If the micro-turbine’s air intake becomes blocked with snow or ice, and there’s no-one around to remove the obstruction, then the machine will shut down and the instruments will go offline.

But the jet engine has been running without incident for several weeks now, and Prof Vaughan believes that if the system proves its mettle, it could become a very useful technology in other locations across the Antarctic.

“We could use it in the field in places where it’s too difficult or just too expensive to run over-wintering stations currently,” he said.

“Halley’s a good test. It’s not an easy place to operate.”

People will go back to the base when sunlight starts to return in the polar south around October/November.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos