A Robot the Size of the World

A Robot the Size of the World

The concept of a robot the size of the world is a mind-bending one, venturing into the realm of science fiction and philosophical thought. To explain it, we can approach it from different angles:

Literally:

- Scale and material: Imagine a gigantic mechanical being, its limbs and body composed of continents, oceans, and the atmosphere itself. Cities could be its circuits, rivers its veins, and mountains its bones.

- Movement and function: The robot’s movements would be on a planetary scale, continents shifting, oceans churning, and winds howling like its breath. Its purpose could be anything from terraforming planets to maintaining the delicate balance of ecosystems.

- Consciousness and agency: Does this world-sized robot have a mind? Does it act purposefully, or is it simply a vast, self-regulating machine? This question delves into the nature of consciousness and sentience on a cosmic scale.

Metaphorically:

- Nature as a machine: The robot could symbolize our understanding of the world as a complex system, with natural processes playing the role of cogs and gears. It might represent the interconnectedness of all things and the delicate balance of forces that sustain life.

- Humanity’s impact on the planet: The robot could be a cautionary tale, reflecting our own impact on the environment. Its immense size and potential for manipulation could highlight the responsibility we hold towards the planet.

- Transcending human limitations: The robot could symbolize the potential for technology to surpass human limitations, to reshape the world on a grand scale. It might spark questions about the ethics and consequences of such power.

Ultimately, “a robot the size of the world” is a concept open to interpretation. It’s a springboard for the imagination, a way to explore our relationship with technology, nature, and our own place in the universe.

Here are some additional points to consider:

- Is the robot visible? Would we be able to perceive it as a single entity, or would we only experience its actions on a local level?

- Is it friendly or hostile? Does it see humanity as a part of itself, or a potential threat?

- What is its ultimate goal? Is it simply maintaining the world, or does it have some grander purpose?

The more you explore these questions, the deeper and more fascinating the concept of a world-sized robot becomes.

I hope this helps explain the diverse ways “a robot the size of the world” can be interpreted and explored.

In 2024, I wrote about an Internet that affected the world in a direct, physical manner. It was connected to your smartphone. It had sensors like cameras and thermostats. It had actuators: Drones, autonomous cars. And it had smarts in the middle, using sensor data to figure out what to do and then actually do it. This was the Internet of Things (IoT).

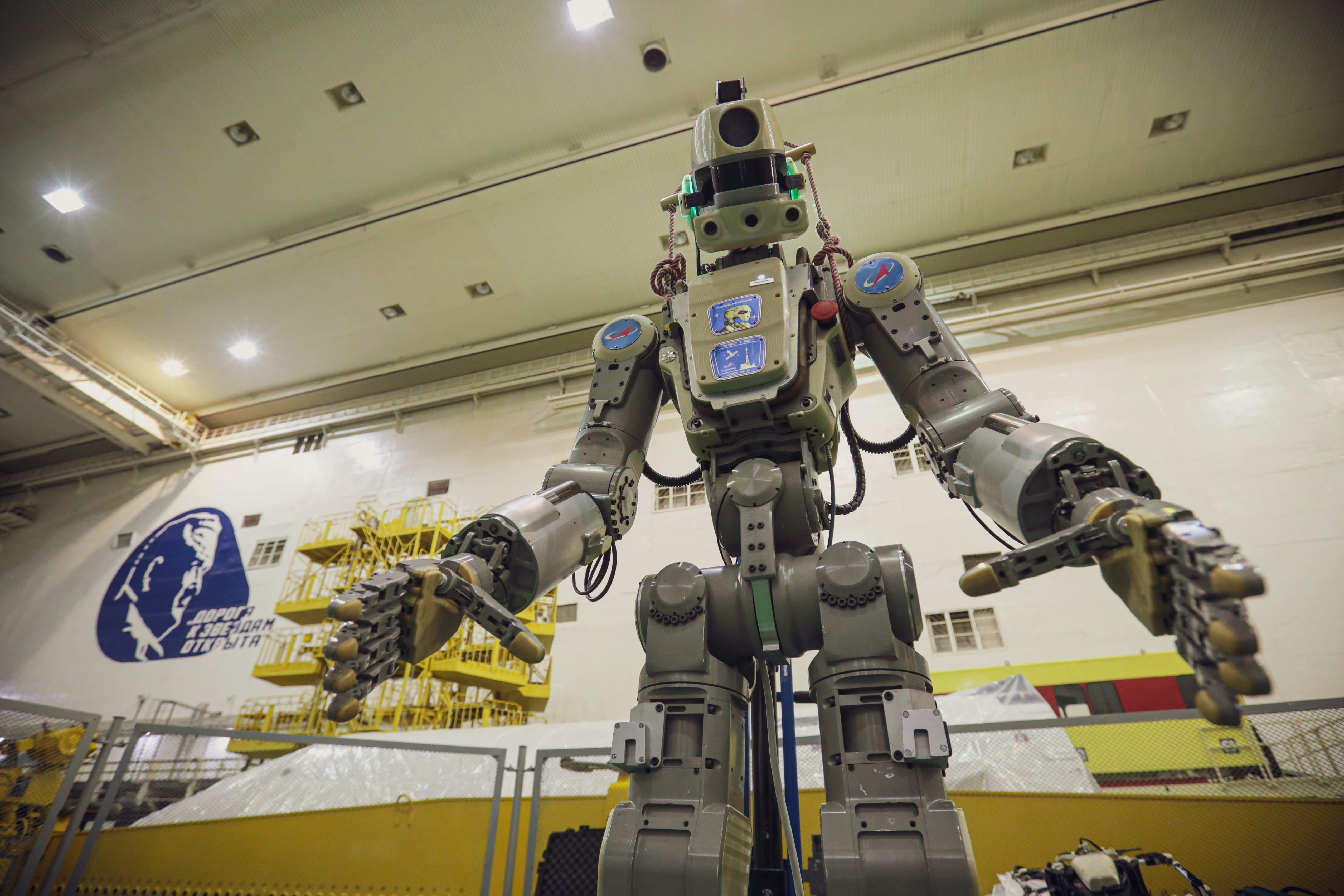

The classical definition of a robot is something that senses, thinks, and acts—that’s today’s Internet. We’ve been building a world-sized robot without even realizing it.

In 2024, we upgraded the “thinking” part with large-language models (LLMs) like GPT. ChatGPT both surprised and amazed the world with its ability to understand human language and generate credible, on-topic, humanlike responses. But what these are really good at is interacting with systems formerly designed for humans. Their accuracy will get better, and they will be used to replace actual humans.

In 2024, we’re going to start connecting those LLMs and other AI systems to both sensors and actuators. In other words, they will be connected to the larger world, through APIs. They will receive direct inputs from our environment, in all the forms I thought about in 2024. And they will increasingly control our environment, through IoT devices and beyond.

It will start small: Summarizing emails and writing limited responses. Arguing with customer service—on chat—for service changes and refunds. Making travel reservations.

But these AIs will interact with the physical world as well, first controlling robots and then having those robots as part of them. Your AI-driven thermostat will turn the heat and air conditioning on based also on who’s in what room, their preferences, and where they are likely to go next. It will negotiate with the power company for the cheapest rates by scheduling usage of high-energy appliances or car recharging.

This is the easy stuff. The real changes will happen when these AIs group together in a larger intelligence: A vast network of power generation and power consumption with each building just a node, like an ant colony or a human army.

Future industrial-control systems will include traditional factory robots, as well as AI systems to schedule their operation. It will automatically order supplies, as well as coordinate final product shipping. The AI will manage its own finances, interacting with other systems in the banking world. It will call on humans as needed: to repair individual subsystems or to do things too specialized for the robots.

Consider driverless cars. Individual vehicles have sensors, of course, but they also make use of sensors embedded in the roads and on poles. The real processing is done in the cloud, by a centralized system that is piloting all the vehicles. This allows individual cars to coordinate their movement for more efficiency: braking in synchronization, for example.

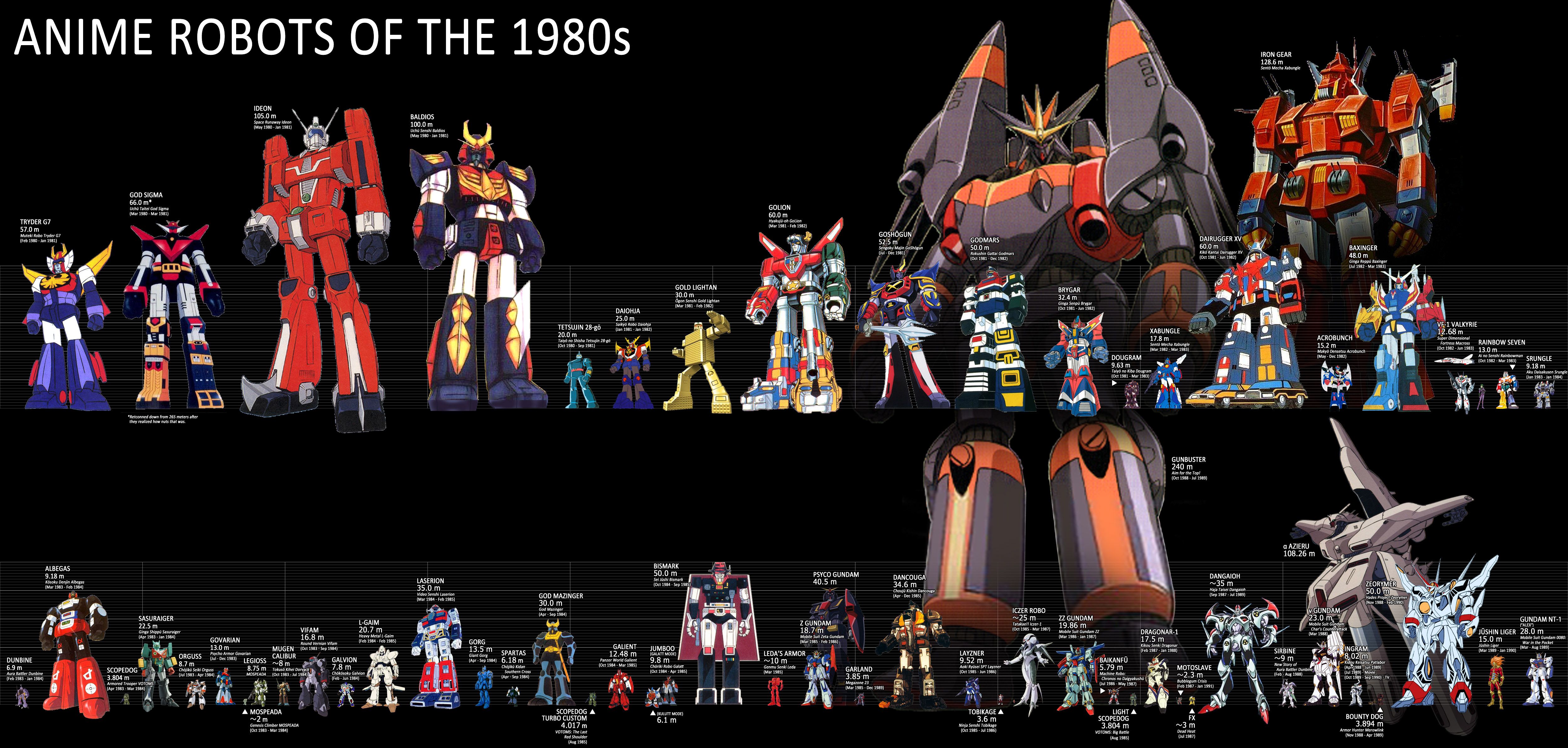

These are robots, but not the sort familiar from movies and television. We think of robots as discrete metal objects, with sensors and actuators on their surface, and processing logic inside. But our new robots are different. Their sensors and actuators are distributed in the environment. Their processing is somewhere else. They’re a network of individual units that become a robot only in aggregate.

This turns our notion of security on its head. If massive, decentralized AIs run everything, then who controls those AIs matters a lot. It’s as if all the executive assistants or lawyers in an industry worked for the same agency. An AI that is both trusted and trustworthy will become a critical requirement.

This future requires us to see ourselves less as individuals, and more as parts of larger systems. It’s AI as nature, as Gaia—everything as one system. It’s a future more aligned with the Buddhist philosophy of interconnectedness than Western ideas of individuality. (And also with science-fiction dystopias, like Skynet from the Terminator movies.) It will require a rethinking of much of our assumptions about governance and economy. That’s not going to happen soon, but in 2024 we will see the first steps along that path.

This essay previously appeared in Wired.