Climate change: Drilling in ‘Iceberg Alley’

Image copyright Thomas Ronge/AWI

Image copyright Thomas Ronge/AWI It sounds a bit like sitting in the middle of the road when there’s a queue of juggernauts coming straight at you.

This is a little overplayed but it’s kind of what an international group of scientists has just set out to do.

The researchers want to position themselves in the centre of “Iceberg Alley” off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and drill into the seafloor.

Huge blocks of ice are likely to come drifting by in the process.

It’s hoped the sediments the researchers recover will tell us something of how the White Continent has changed in the past and how its kilometres-thick ice sheet might react in the future in what’s projected to be a much warmer world.

Expedition 382 of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) left Punta Arenas in Chile on Monday. Using the drill ship, the Joides Resolution (JR), the team will core a number of seafloor locations right in the middle of Iceberg Alley.

The scientists are looking for the “rafted debris” that’s been dropped by giant bergs as they head north from the Peninsula towards the South Atlantic.

This detritus of dust, dirt, and rock was originally scraped off the continent by the ice when it was part of a glacier, before it broke away to become an iceberg.

And through the wonder of modern geochemistry, it’s possible to date this material and even to tie it to the specific locations in Antarctica.

Image copyright Thomas Ronge/AWI

Image copyright Thomas Ronge/AWI The really helpful thing from the scientists’ point of view is that they only need go to the alley to get a very broad view of past Antarctic behaviour.

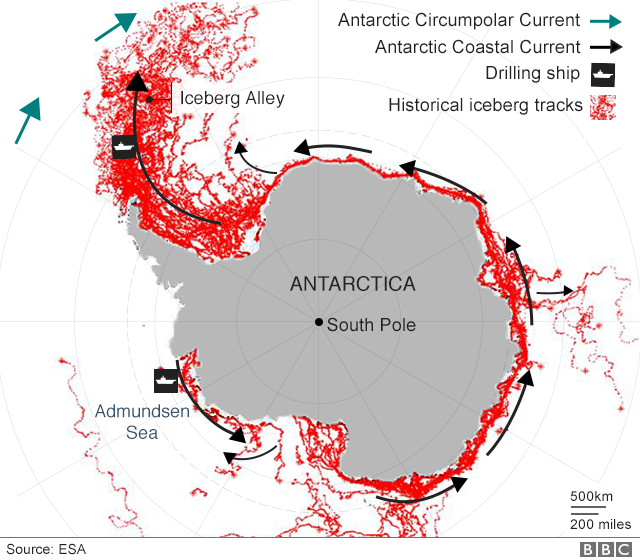

It works like this: Bergs when they calve will bump anti-clockwise around the coast in the direction taken by near-shore currents. But when they reach the Peninsula – that’s when they encounter the big clockwise flow of water known as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

Image copyright Thomas Ronge/AWI

Image copyright Thomas Ronge/AWI The bergs are then entrained and head north.

And just standing in the middle of this busy highway, as the JR now intends to do, means you get to sample the widest range of material dropped from historical bergs on their slow drift up into the South Atlantic.

In very simple terms: the more ice blocks that passed through the alley in any particular period in the past, the more unstable the Antarctic was likely to have been during that time.

In other words, the thickest layers of dropped stones and dust deposited on the ocean floor should relate to the warmest phases of ancient Antarctica.

There’s quite a bit of oversimplification in this story, not least the recognition that the alley is dominated by bergs from the East of the continent – but the general picture holds.

Image copyright Tim Fulton/IODP/JRSO

Image copyright Tim Fulton/IODP/JRSO The JR expects to pull up hundreds of metres of sediment core covering the past 20 million years.

“A key interval of interest will be the Late Pliocene Warm Period (about 3-4 million years ago),” said expedition co-lead investigator Prof Maureen Raymo from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, US.

“This was when carbon dioxide was 400 parts per million (ppm) in the atmosphere – approximately similar to what it is today. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to work out what global sea-level was doing at that time because obviously that would speak directly to the question of whether East Antarctica loses mass or gains mass in a slightly warmer climate.” The latter is possible if a warmer atmosphere triggers more snowfall.

Image copyright Clayton Furman/IODP/JRSO

Image copyright Clayton Furman/IODP/JRSO Another period of keen interest is that of the Early Pleistocene – from 2.5 million to 800,000 years ago. It’s a phase in Earth history when Ice Ages on the planet are known to have come and gone on roughly 41,000-year cycles.

This had something to do with the shifting nature of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, but has yet to be fully explained.

“I’ve proposed that Antarctica didn’t transition to the ice sheet we see today until about 800,000 years ago, and prior to that there were maybe many sectors of the ice sheet that looked like modern Greenland with the ice margin on land,” Prof Raymo told BBC News. Today’s Antarctica has its glaciers terminating in the sea.

“We’ll definitely get sediments from this time,” she added.

Image copyright Pete Bucktrout/BAS

Image copyright Pete Bucktrout/BAS If the current cruise is focussed on past behaviour in East Antarctica, a complementary drilling effort should fill in much of the narrative in the West of the continent.

The JR has only recently finished drilling sediment cores in the Amundsen Sea area of the continent.

IODP Expedition 379 cored to a depth of 800m, which likely gets back to the Late Miocene, or about 6 million year ago.

“This is the sector of the Antarctic Ice Sheet – more than any other area – that is changing before our eyes,” explained 379’s co chief scientist, Dr Julia Wellner from the University of Houston.

“While we have some ideas on why this is happening, it’s not well understood yet; we’ve only been watching it for a few decades.

“So that’s why we need these longer-term records, to get a real insight on what’s occurring now and how things could change in the future.

“But it’s not easy. There were times on our cruise when we thought we were in Iceberg Alley because there were so many bergs about, and every time one approaches you have to abandon your hole, wait for the berg to pass, and then return to resume drilling.”

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos