ULEZ: How does London’s new emissions zone compare?

Media playback is unsupported on your device

London’s tough new Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ) is the latest – and one of the strongest – steps yet taken to limit emissions of pollutants from cars, vans and trucks. So how does it compare with other cities in Europe and the rest of the world?

CAZ? LEZ? ULEZ? What do they all mean?

These are all different ways of describing geographical areas of cities or towns that have placed restrictions on the use of vehicles, with the goal of tackling air pollution. A CAZ is a clean air zone, a LEZ is a low-emissions zone. Now we have London with the world’s first ULEZ, or ultra-low emissions zone.

In the UK, CAZs are areas that can decide to use charging as a means of cleaning the air, but don’t have to. If they do impose some form of charging for the most polluting vehicles, they are called a LEZ.

Across Europe there is less clarity about definitions, and LEZ is the term widely used to describe around 250 areas in different cities, with considerable variation.

“Not all LEZs have been created equal,” said Yoann Le Petit from the research group Transport & Environment.

“In Brussels, in terms of coverage, it’s quite a large LEZ, but in terms of ambition level, it’s very low. It started last year, banning Euro 1 cars (registered before 1992). These are very old vehicles; you hardly see them on the street.

“You also have a very high ambition LEZ in Madrid and the one just introduced in Stuttgart, but there is no agreed definition of what an LEZ is.”

Who’s got the most restricted areas?

Across Europe, Italy has the most low-emissions zones – some of them permanent, many of them seasonal. There are also around 80 in Germany, 14 each in the Netherlands and the UK. France has also 14 LEZs, but most of these are emergency schemes that are enforced on a daily basis when there are pollution peaks.

What’s happening in the rest of the world?

There are initiatives under way across all continents. Some are more successful than others.

Tokyo was one of the first cities to ban diesel vehicles, starting back in 2000.

Seoul in South Korea only introduced measures in 2017 to ban diesel cars that failed to meet emissions standards.

Bogota in Colombia has been working since 1974 to get cars off the streets. Every Sunday sees large numbers of roads closed until 2pm. They have also attempted to restrict cars based on number plates with less success.

Mexico city has also developed restrictions based on number plates and by banning cars on Saturdays. However, a study from 2017 says that it hasn’t worked as well as hoped because people car-pooled, used taxis or bought extra vehicles.

In the US, San Francisco has plans to ban cars on Market Street; and Los Angeles, Denver and Charlotte are thinking about how to reduce emissions in the future. But no American city has yet banned diesel cars in any form.

Surprising lessons from the world’s oldest LEZ?

One of the most curious things to come out of the introduction of a LEZ in Sweden in 1996 was the demand from trucking companies to make them bigger.

“Before the introduction, some hauliers were really angry about it,” said Anders Roth, formerly the civil servant in charge of the Gothenburg LEZ.

“Then they realised it wasn’t that bad and the big hauliers who invested in new vehicles realised they could make more money from having a good environmental profile, and they wanted the zone made bigger.”

The world’s first LEZs for vehicles were introduced in Gothenburg, Stockholm, Malmo and Lund in Sweden back in the mid 1990s. The restrictions put in place were targeted at the most polluting diesel trucks and buses in the city centre. Essentially, any vehicle over 3.5 tonnes.

Private cars were not included; they’re still not banned.

“The next step would be to include cars, but that’s a more controversial question in Sweden. We already have congestion charging in Gothenburg and Stockholm, but politicians are reluctant to enforce more regulations,” said Mr Roth.

He believes that because the Swedish cities started earlier, they have had to place fewer restrictions on vehicles to achieve cleaner air.

“We started early and people got used to it and now it’s normal – people would think it would be silly to take it away.”

He’s a supporter of the London ULEZ.

“I think that’s the best way to go. You don’t have to ban vehicles totally if they are not really bad; you can have the same effect but without the same high cost for society.”

Do these restrictions make a big difference?

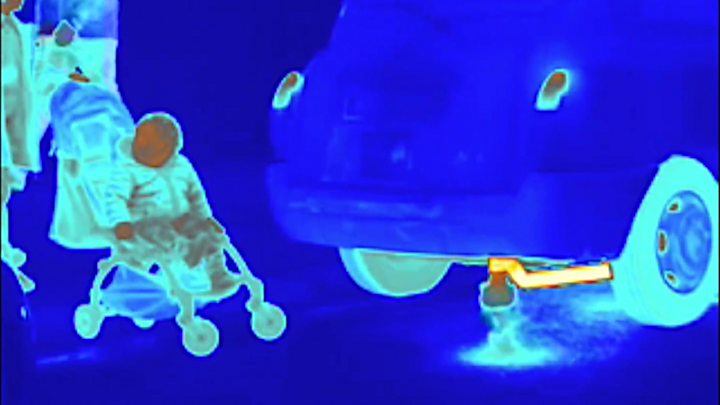

Undoubtedly all the zones are having an impact – but the scale of the difference varies, depending on the type of pollutant. They’ve worked well with diesel particulates which the World Health Organization has linked to cancer.

“They have made a huge difference with all forms of particulate matter,” said Lucy Sadler, who previously led the London Mayor’s air quality team and now runs a website that collects information on how cities are tackling air pollution.

“Nitrous oxides (NOx) are harder, no thanks to vehicle manufacturers.”

“If you look at Milan, which has a low-emissions zone and a congestion charge combined, they’ve reduced NOx by 10%, they reckon. That’s huge in a city because there’s not that many things you can affect.

“A low-emissions zone won’t be a single magic wand, but it can usually be the biggest single measure.”

Is London’s new zone really the “toughest” in the world?

It’s very hard to say definitively as different cities have different levels of restriction. Certainly, it is one of the most ambitious among the world’s largest cities. But some critics say that it could be tougher by banning polluting vehicles instead of just charging them.

Some experts believe this is down to the level of authority in the Mayor’s hands.

“In London they have the power to charge for it; others have the right to ban,” said Kate Laing from C40 Cities, a group of major world cities committed to tackling climate change.

“But if you are willing to drive and pay the charge three days a week instead of five days a week – that is still making gains in air quality.”

Apart from London, two cities in Europe are said by observers to be the most restrictive.

In Madrid, there is a zero-emissions zone since last November, about the same size as the new London ULEZ.

To drive into the Madrid zone, you have to have authorisation and that is only given to zero-emissions vehicles such as electric cars. However, residents are given an exemption that they can continue to use their existing cars until they get a new one.

It is more relaxed for residents, say experts, because it was introduced with much less lead time than London,

“Madrid is a small zone but it is very ambitious,” said Yoann Le Petit. “They could already see a NO2 reduction of around 40%. Even outside the LEZ, they saw a slight decrease in traffic, as people know they won’t be able to go through the city centre. They even saw a slight increase in business in the zone.”

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Oslo also has very ambitious plans. The city has already removed 700 car parking spaces to create bike lanes and small parks. It also has a zero emissions zone in the centre of the city.

Do local governments make money from these schemes?

According to experts, low-emissions zones don’t make money.

“The more you enforce, the more expensive it gets,” said Lucy Sadler.

“If you fine someone £40, it won’t cover the cost to enforce it. They don’t make money. It’s a myth that some organisations like to promote, but it’s absolutely not based on fact.

“Combined congestion charging is different. Across Europe, London is best-practice as the money raised is spent on local public transport. In other countries, it’s not the case.”

Where do we go from ULEZ?

To zero, most likely. The direction of travel is to increase the size of low-emissions zones, and then, over time, to go to zero emissions. This means that only electric cars, or vehicles powered by battery or hydrogen, for example, would be allowed in.

“Zero is a big step from low. It will require serious investment in electric vehicles and hydrogen, and shifts towards more walking, cycling and public transport,” said Kate Laing from C40 Cities.

“In London, the Mayor’s transport strategy is to try to achieve 80% of trips across London in walking, cycling and mass transport by 2040; the ULEZ is feeding into a long-term vision of the city by 2040.”

This thrust is not just because of air quality; it’s also down to climate change. Emissions from transport are proving very tough to curb, and will require continued restrictions on internal combustion engines.

“Increasing numbers of cities are saying zero-emissions zones,” said Lucy Sadler.

“In terms of where we are going – this is the final destination,” said Yoann Le Petit.

Follow Matt on Twitter.