So where did the Mars methane go?

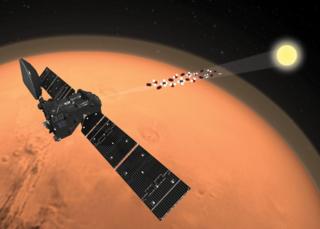

Image copyright ESA

Image copyright ESA

The mystery of methane on Mars just got a whole lot more complicated.

The gas, which on Earth is produced in large part by living things, has previously been detected on the Red Planet by remote observation, and on the ground by Nasa’s Curiosity rover.

But the most sensitive search at Mars so far, undertaken by a joint European-Russian satellite, has drawn a blank.

And this Trace Gas Orbiter, as it’s called, is capable of seeing methane at fantastically low levels.

Even when the concentration is only a few tens of molecules in every trillion molecules of Martian air, the TGO should still to be able to identify the presence of CH4, if it’s there.

The fact that the satellite couldn’t when probing the atmosphere in April to August last year raises some difficult questions and some fascinating possibilities.

Other stories from EGU 2019

Inevitably, some people will argue that the earlier detections were mistaken, but Oleg Korablev from the Space Research Institute at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow will not be among them.

“We prefer not to criticise others’ results; we can only claim the accuracy of our results,” the TGO scientist told BBC News.

“We just report the data and leave it up to the theoreticians to try to explain what is going on.”

Curiosity’s sampling in 2013 in equatorial Gale Crater found spikes of methane in the air at a few parts per billion.

This was ostensibly confirmed by concurrent observations from orbit by another satellite, Europe’s Mars Express spacecraft.

So, if it’s accepted that the methane really was there in 2013 and that TGO is the gold standard at Mars today – it requires scientists now to identify a hitherto unrecognised process that can rapidly remove CH4 from the atmosphere in a very short space of time.

This is the working hypothesis, says Dr Manish Patel, another TGO scientist from the UK’s Open University.

“If we take the previous measurements at face value, and we obviously believe our own results – then there’s something going on in the atmosphere between those two points in time, and it’s something we don’t predict.

“We expect methane to hang around in the atmosphere of Mars for hundreds of years. It’s destroyed by sunlight, but it’s destroyed over relatively long time-scales in terms of human observation. Whatever was there before should still be there today, even if at a diluted level.”

It’s as if we now have a double puzzle.

People had been debating from where on the planet methane could emerge, with the tantalising prospect that CH4-producing microbes might be the source. Now, they will have to debate where the methane is going; what might be its “sinks”.

Some sort of chemical interaction would be one answer, but Håkan Svedhem, the European Space Agency’s project scientist on TGO, says people shouldn’t be downhearted about the prospects for life on the planet if methane is eventually determined not to be present.

“We’ve got a bit fixated by methane because on Earth we all know that more than 95% of the methane comes from biological sources. But there are abundant forms of life that do not produce methane,” he told BBC News.

The Trace Gas Orbiter arrived at the Red Planet in October 2016, but then took a further year to manoeuvre itself into its proper science orbit at an altitude of 400km above the surface.

Staring in April last year, it began its systematic search of the atmosphere, using the onboard spectrometers NOMAD and ACS.

These measure the constituents of Martian air by looking through the atmosphere towards the Sun. Different molecules absorb the light in characteristic ways.

The precision of this solar occultation method enables TGO to set an upper limit for the methane at just 12 parts per trillion. In other words, if the methane is there, it has to have a lower concentration than this.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

The mission team is reporting its latest observations here at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly.

The group also has some papers being published in the journal Nature and in the the Proceedings of the Russian Academy of Science.

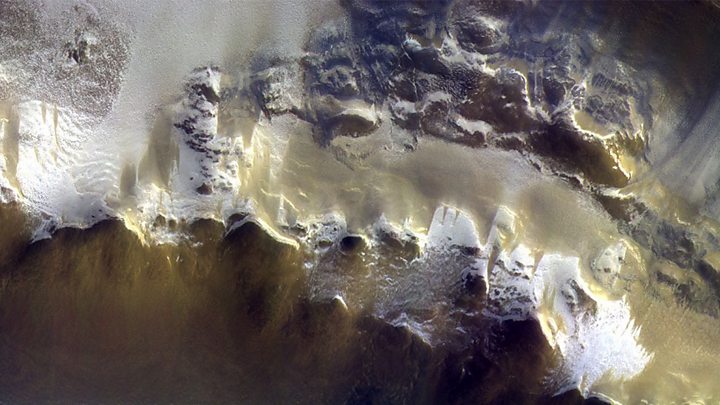

Other results include an exquisite description of how water was taken high into the atmosphere during the recent global dust storm on the planet; and a new map of sub-surface water derived from the satellite’s neutron spectrometer.

This map has greater resolution than any survey before it and, aside from the obviously water-rich permafrost of the polar regions, detects some previously unknown “wet” regions at the equator.

These could be important to future surface robots looking for evidence of present-day microbial life, and for astronauts in need of local water resources.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos