How do you learn to drive on Mars?

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Time is of the essence. It’s now little more than a year until the Rosalind Franklin rover is sent to Mars.

Engineers across Europe and Russia are busy assembling this scientific vehicle, and the hardware that will both carry it to the Red Planet and put it down safely on the surface.

In parallel to all this are the ongoing rehearsals.

These are needed to ensure controllers can easily and efficiently operate the robot from back here on Earth.

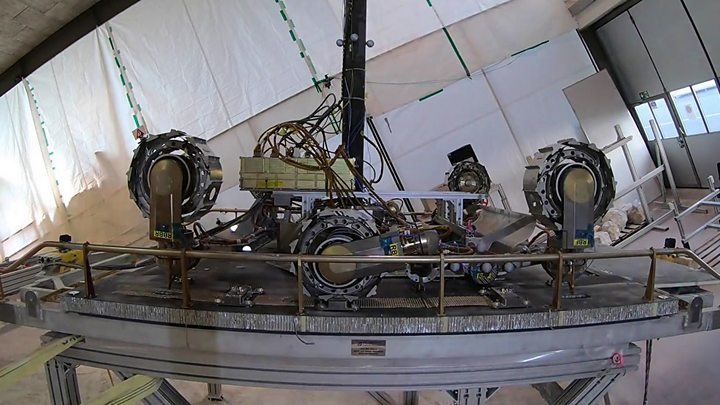

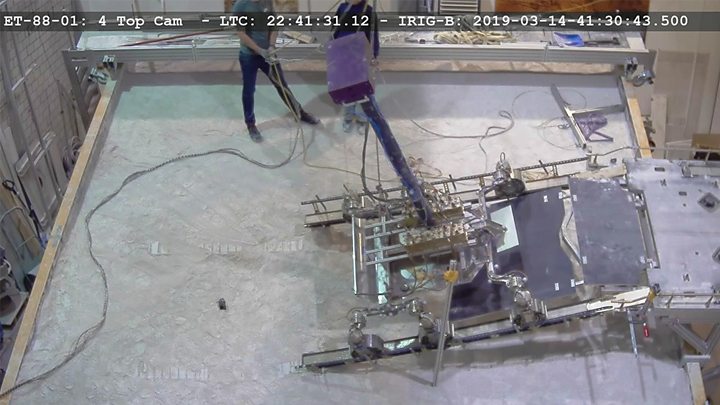

The videos on this page show the latest locomotion verification tests that have been conducted at the RUAG company in Switzerland.

How will the rover stand up on its landing platform and roll down the ramps that take it on to the dusty, rocky terrain of Mars?

How will it negotiate any boulders at the targeted equatorial touchdown location of Oxia Planum?

And how will Rosalind Franklin cope with steep slopes?

These questions have to be answered now, before the rover’s rocket blasts off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in July/August next year.

The robot is a joint project of the European and Russian space agencies. It will roam an ancient terrain, looking for evidence of past – perhaps even present – life.

Key to this search will be a drill that will pull up rocky samples from up to 2m below the surface. It’s underground – away from radiation – that we think life might have a chance on Mars.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Those samples will be delivered to a sophisticated suite of instruments that live inside a sterile box known as the Analytical Laboratory Drawer.

The ALD has just gone through its own test programme in Turin, Italy, and is now sitting in a cleanroom at Airbus in Stevenage, UK, waiting to be bolted on to Rosalind Franklin. Integration of the ALD will likely take place next week.

Engineers at Stevenage have a deadline of July/August to assemble all the robot’s components and get the finished vehicle out the door.

Significant outstanding items sill to be attached include the bogey system (the locomotion chassis and wheels) and the British camera system (PanCam) that will survey Oxia Planum. This equipment will sit atop a mast.

From southern England, the completed rover will travel to southwest France, to Toulouse, where it will be “shaked and baked” at another of Airbus’s facilities. This “environmental testing” will demonstrate the robot can handle the vibrational and temperature extremes it will experience on the flight to Mars.

From Toulouse, Rosalind Franklin will travel across France to Cannes. It’s on the Côte d’Azur that the Franco-Italian aerospace company Thales Alenia Space will do the all-important final fit-check, bringing together the rover, its Russian “Kazachok” landing system (built by NPO Lavochkin), and its German cruise vehicle (from OHB-System) which will manage the journey from Earth to Mars.

Assuming all that goes off without a hitch, everything heads to Baikonur and launch preparations.

Fourteen months really is no time at all.

The rover’s name: Who was Rosalind Franklin?

In 1952, Rosalind Franklin was at King’s College London (KCL) investigating the atomic arrangement of DNA, using her skills as an X-ray crystallographer to create images for analysis.

One of her team’s pictures, known as Photo 51, provided the essential insights for Crick and Watson to build the first three-dimensional model of the two-stranded macromolecule.

It was one of the supreme achievements of 20th Century science, enabling researchers to finally understand how DNA stored, copied and transmitted the genetic “code of life”.

Crick, Watson, and KCL colleague Maurice Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize for the breakthrough.

Franklin’s untimely death meant she could not be considered for the award (Nobels are not awarded posthumously). However, many argue that her contribution has never really been given the attention it deserves, and has even been underplayed.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos