Mars: The box seeking to answer the biggest question

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Is it possible? Is there life on Mars?

Ever since the Mariner 4 probe made the first successful visit to the Red Planet – a flyby in July 1965 – we’ve sent a succession of missions that have given us all sorts of fascinating information about Earth’s near neighbour – but not the answer to the only question that really matters.

So, take a look at the technology that may finally change the game.

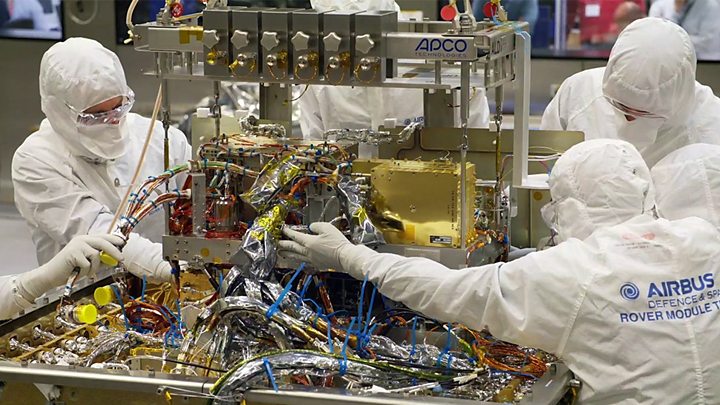

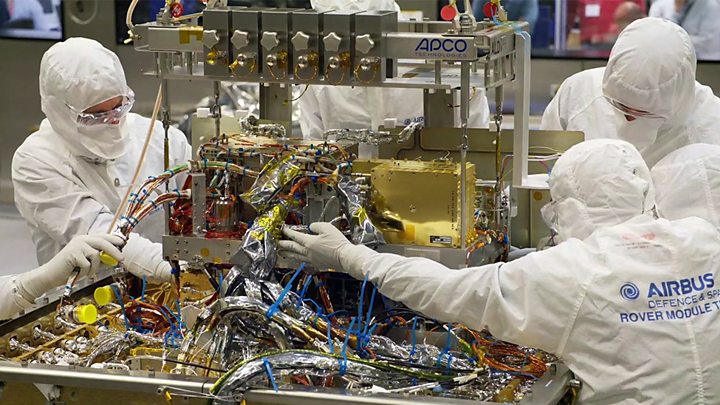

This is the Analytical Laboratory Drawer, or ALD – a sophisticated three-in-one box of instruments that will examine rock samples for the chemical fingerprints of biology.

On Thursday, it was gently lifted by crane and lowered into the ExoMars “Rosalind Franklin” rover, the six-wheeled buggy that will carry it across the Oxia plain of Mars in 2021.

The 300kg robot, which is being developed jointly by the European and Russian space agencies, will have a drill that can dig up to 2m below the planet’s dusty surface.

The tailings pulled up by this tool will be handed through a door to the ALD, where the various mechanisms inside will then crush and prepare powders that can be dropped into small cups for analysis.

It will be a forensic examination, looking at all aspects of the samples’ composition.

All previous rovers have skirted the big question. They’ve essentially only asked whether the conditions on Mars today or in the past would have been favourable to life – if ever it had existed. They haven’t actually had the necessary equipment to truly detect biomarkers.

Rosalind Franklin will be different. Its 54kg ALD has been built specifically to look for those complex organic molecules that have their origin in life processes.

Thursday’s integration was slow and deliberate, understandably: the ALD is in many ways the key element of the Rosalind Franklin mission.

“It is wonderful to see the heart of the rover has now been installed,” said Sue Horne, the head of space exploration at the UK Space Agency.

“The Analytical Laboratory Drawer is the key location for Martian sample testing on the rover, allowing us to understand the geology and potentially to identify signatures of life of Mars. I can’t wait to see what discoveries lie in store for this British-built rover.”

Engineers at Airbus UK are now working three shifts a day to get the rover finished.

Although it doesn’t look much like a vehicle at the moment, virtually all the components have now arrived at the Stevenage factory.

They’re sitting on shelves around the edge of the cleanroom in bags, waiting their turn in the assembly sequence.

There are one or two outstanding items, however, including the rover’s British “eyes”.

This is the camera system, or PanCam, which will sit atop a mast and guide the robot on its trail of investigation.

“We’ve just held the delivery review board this week and PanCam should be coming to us in the next few days,” said Chris Draper, the flight model operations manager at Airbus.

“We know everything will go together; that’s the beauty of systems engineering. Every single part of the rover has been modelled in 3D, and everyone works to interface control drawings. Assuming we all do that then we know the ALD, for example, will fit perfectly into the rover.”

The Stevenage team has a hard deadline of the beginning of August to get the finished Rosalind Franklin rover out the door.

It has to go to the company’s Toulouse facility for a series of tests that will ensure the design is robust enough to cope with the severe shaking experienced on a rocket ride to Mars.

Further fit-checks then follow in France before shipment to the launch site at the famous Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

Lift-off has to occur in July/August next year. This date is immoveable: you only go to Mars when it’s aligned with Earth and the windows of opportunity have an interval of 26 months.

The rover’s name: Who was Rosalind Franklin?

In 1952, Rosalind Franklin was at King’s College London (KCL) investigating the atomic arrangement of DNA, using her skills as an X-ray crystallographer to create images for analysis.

One of her team’s pictures, known as Photo 51, provided the essential insights for Crick and Watson to build the first three-dimensional model of the two-stranded macromolecule.

It was one of the supreme achievements of 20th Century science, enabling researchers to finally understand how DNA stored, copied and transmitted the genetic “code of life”.

Crick, Watson, and KCL colleague Maurice Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize for the breakthrough.

Franklin’s untimely death meant she could not be considered for the award (Nobels are not awarded posthumously). However, many argue that her contribution has never really been given the attention it deserves, and has even been underplayed.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos