Antarctic glaciers to honour ‘satellite heroes’

A series of glaciers in the Antarctic are being named after the satellites that have revealed the changing state of the White Continent.

The spacecraft, from Europe, the US and Japan, have all contributed important observational data which confirms a picture of accelerating ice loss.

They include the pioneering American Landsat series of satellites and Europe’s new Sentinel fleet.

Their namesake glaciers run parallel to each other in Palmer Land.

This is a sector on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

It’s an area studied by Dr Anna Hogg, who was frustrated that the glaciers she was looking at were known only by their coordinates on a map.

The Leeds University scientist proposed the satellite names idea to the UK Antarctic Place-names Committee.

Its members accepted the suggestion, which was then formally approved by the Government of the British Antarctic Territory.

“Satellites are the heroes in my science of glaciology. They’ve totally revolutionised our understanding, and I thought it would be brilliant to commemorate them in this way,” Dr Hogg told BBC News.

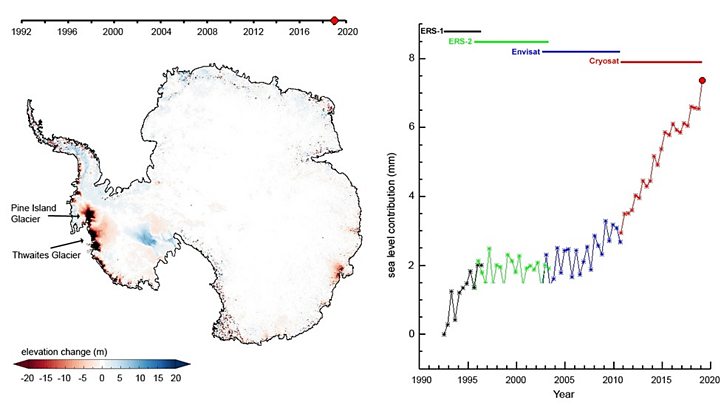

Just last month, she and colleagues from the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM) used the full history of height measurements made by Europe’s orbiting radar altimeters to show that almost a quarter of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is now losing more ice than it can replenish through new snowfall.

The glacier names will in future be used on all British maps, charts and publications; and they have also been put up to the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) for inclusion in its international directory, or gazetteer.

This should lead to all other nations using the names, too. Safe operations require that there is no confusion over what a location is called during an emergency.

The ‘satellite heroes of glaciology’

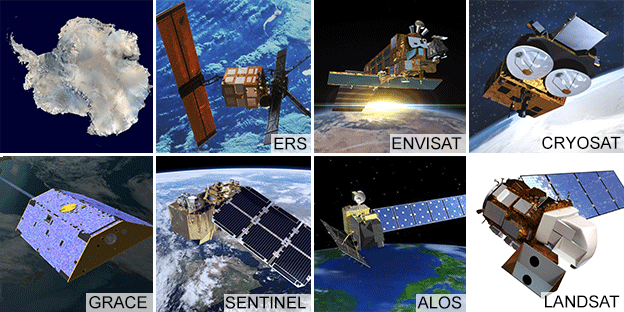

ERS Ice Stream: Two “European Remote Sensing” satellites were launched in the 1990s. They started the European Space Agency’s (Esa) continuous monitoring of the continent from orbit.

Envisat Ice Stream: The big all-purpose satellite worked for 10 years up to 2012. One of its first jobs was to study the collapsing Larsen-B Ice Shelf, at the time one of the largest such structures in Antarctica.

Cryosat Ice Stream: Esa launched a dedicated polar observer in 2010. Its high-resolution radar altimeter has significantly reduced the uncertainties over the loss of ice, which is occurring predominantly in the West.

Grace Ice Stream: Two US-German missions have measured Antarctica’s gravity field. They’ve essentially weighed the ice, to give an independent check on the imaging and elevation studies of other satellites.

Sentinel Ice Stream: The European Union-owned fleet of satellites uses multiple sensors to study Antarctica. The satellites are a long-term commitment and will maintain the data-sets initiated by ERS, Envisat and Cryosat.

Alos Ice Rumples: The “Advanced Land Observing Satellite-1” was a Japanese mission from 2006 to 2011. Its inclusion in the named group emphasises the international dimension of Antarctic research.

Landsat Ice Stream: The grandaddy of observing systems began operations in the early 1970s. The eight Landsat spacecraft have been integral to mapping the continent and building ice velocity charts.

The continent is so remote and so vast – 14 million sq km – and its environment so hostile that satellites are really the only way to get an overarching picture of what’s going on.

Multiple satellites overfly the polar south daily with a variety of instruments, to monitor its weather, to track the speed and height of its glaciers, and to stand watch for the production of huge icebergs that might pose a risk to shipping.

Mark Drinkwater, Esa’s senior advisor on cryosphere and climate, underlined the importance of nations working together in Antarctica.

Only coordinated planning for the long term could produce the right data-sets to answer the big research questions, he said.

“This gesture, by baptism of glaciers with the names of these ground-breaking satellites, is a mark of recognition of the increasing importance of Earth Observation data in today’s climate science debate,” he told the BBC.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

To read the names in Antarctica is, in many ways, to read its exploration history.

On the Antarctic Peninsula, for example, you will find many Belgian names as a consequence of Adrien de Gerlache’s expedition at the end of the 19th Century; and many French names that reflect the exploits of Jean-Baptiste Charcot at the beginning of the 20th Century.

“Themes have been encouraged; they work well,” said Dr Adrian Fox, the secretary of UK Antarctic Place-names Committee.

“Greek mythology, composers, pioneers of nutrition research or equipment that’s useful in Antarctica. That kind of thing. So, the ones coming from Anna Hogg are really nice because they’re a set of names that are really relevant to Antarctic affairs.”