Early animal had ‘complex behaviour’

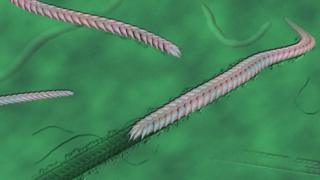

Image copyright Zhe Chen / Shuhai Xiao

Image copyright Zhe Chen / Shuhai Xiao A millipede-like creature from 550 million years ago is among the earliest examples of an animal showing complex behaviour.

Long before the dinosaurs walked the Earth, the four-inch long creature dragged its body along a muddy sea floor and became fossilised.

The animal died right next to its trail, giving scientists the rare opportunity to link it to the track it made.

The fossil was found in eastern China.

It’s among the earliest examples of continuous, directed movement by animals. Researchers say the specimen may hint that a form of complex behaviour had already evolved in these earliest animals half a billion years ago.

The animal appears in rocks that belong to a slice of geological time known as the Ediacaran. This period is known for the appearance of very early multicellular life forms.

“It’s the continuous trails that are most abundant in the Ediacaran rocks. A lot of times they’re not preserved with the animal that made them,” co-author Prof Shuhai Xiao, from Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, US, told BBC News.

“So it’s almost impossible to say what animals made these continuous trails, unless you have the animals preserved together with the trails.”

Prof Rachel Wood from the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved with the study, called the specimen a “milestone of complexity”.

She added: “It’s simply a spectacular fossil. It’s spectacular because of its age. It’s Pre-Cambrian – it’s of an age that we now call Ediacaran.

“But what’s particularly noteworthy about it is that it’s combining a trace – the movement of an animal across the ancient sea floor – with the actual animal that did it. Without any doubt we can assign the trace to the trace-maker.”

She said another thing made the fossil remarkable: “They show that a type of complex behaviour had evolved before the Cambrian (when multi-cellular life exploded into a wide variety of forms) the ability to move over the sea floor.”

Prof Wood explained that this specimen tied the earlier Ediacaran organisms more closely to those found in the later Cambrian.

The animal has been named Yilingia spiciformis – which translates to spiky Yiling bug. Yiling is the Chinese city located near the discovery site.

The four-inch-long (10cm) animal measured about a quarter-inch (0.6cm) to an inch (2.5cm) wide. It dragged its body across the ancient marine mud, but examination of the trail shows that it rested along the way.

“Though it’s not well-preserved, it has the hint that it has a front and a back… so this animal has already got some sense of unidirectional movement.” said Prof Wood.

“The fact that it’s segmented tells us that there’s some connection between segments…”

Segments are the repetitive units that make up the bodies of arthropods, the large group of animals that includes everything from lobsters to butterflies and millipedes.

However, apart from the fact the animal seems to have a defined head and tail, most of its segments “are fundamentally similar to each other”, said Shuhai Xiao.

This differs from modern segmented animals where the segments are regionalised, making them rather distinct from one another.

“It gives us a more complete picture about the transition from simple repetition to advanced segmentation,” said Prof Xiao.

In the past, the creatures that lived in the Ediacaran had been extremely difficult to classify. In fact, their position on the tree of life has been one of the greatest mysteries in palaeontology.

They were variously classified as lichens, fungi, or an intermediate stage between plants and animals.

But last year, scientists discovered some Ediacaran fossils retained traces of the molecule cholesterol – a hallmark of animal life.

“Just 20 years ago, some of us still thought the Ediacaran fossils were unrelated to animals. There was a hypothesis called the ‘Ediacaran garden’, but I think what we’re seeing now is an ‘Ediacaran zoo’,” said Shuhai Xiao.

“The challenge is now to place these in a family tree of animals.”

As for what type of animal the Ediacaran fossil represented, Prof Wood said: “It’s very difficult to know what this animal was. The authors of the paper suggest it might be related to worms, or to arthropods – the group that includes crabs and lobsters and insects today.

“But it’s almost certainly a primitive representative of one of these two groups – even a precursor to both of these groups before they diverged. So it’s rather hazy as to exactly what type of animal this is. But there’s no doubt it’s a bilaterian – an animal with bilateral symmetry, which is quite unlike more basal invertebrates, things like sponges and corals.”

Follow Paul on Twitter.