Anak Krakatau volcano collapse: ‘Warning signs were there’

Taking all the available data, it was clear something was amiss with the tsunami-generating volcano. …

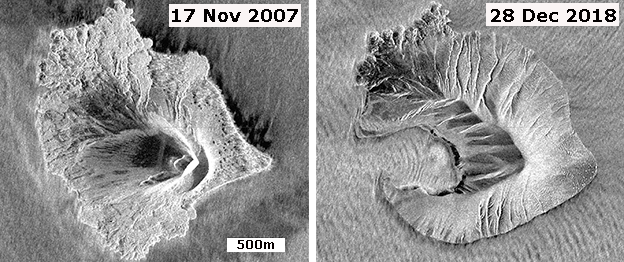

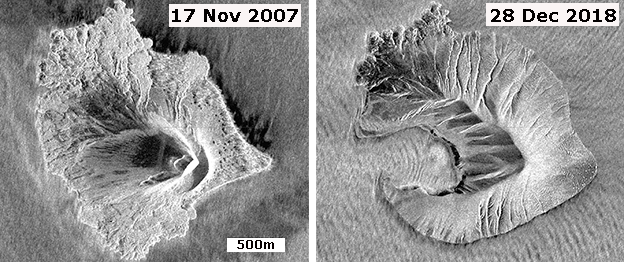

Image copyright TerraSAR-X/DLR/GFZ

Image copyright TerraSAR-X/DLR/GFZ Anak Krakatau, the Indonesian island volcano that collapsed last December triggering a huge tsunami, did produce clear warning signals before the event.

That’s the assessment of a German-led team which has reviewed all the data.

The scientists say satellites in the months leading up to the catastrophe had observed increased temperatures and ground movement on the volcano.

Earthquake and infrasound activity was also detected two minutes prior to the collapse of Anak’s southwestern flank.

When this mass slid into the sea, it sent a wall of water, up to 4m high, around the Sunda Strait.

More than 400 people died in 22 December tragedy; a further 7,000 were injured and nearly 47,000 were displaced from their homes.

Thomas Walter, from the German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ in Potsdam, said any of the different signals viewed individually could not have been used to predict what happened at the island volcano, but taken together they might well have raised a red flag.

“If you took any of the sensors on their own, the interpretation would not be robust, but by pulling together all of the different sensors we can draw a picture of the cascade that was going on,” Dr Walter told BBC News.

The team noted that the volcano was experiencing its greatest eruptive phase in 20 years in 2018; that its southwestern flank had begun edging seaward from January onwards; that there was an intense phase of thermal activity initiated on the 340m-high mountain in June, and that there had been an increase in the island’s surface area in the months leading up to the collapse.

There was also significant seismic behaviour just before the collapse. Perhaps an earthquake, maybe an explosion; it’s not clear.

But what was interesting, explained Dr Walter, was that this seismic signal did not go down to zero. And when it picked again, it displayed a low frequency that is characteristic of landslide behaviour.

A couple of minutes further on in time, the frequency changes again, which the team interprets as a barrage of volcanic explosions – as “the cork comes off the top of the bottle”.

As to how the lessons learned at should be used at other vulnerable volcanoes, Dr Walter said the kind of flank movement observed Anak Krakatau could be regarded as a potential long-term precursor.

Radar satellites will detect this deformation and a number of groups around the world are even developing automated systems where algorithms hunt through the spacecraft data for evidence of anomalous activity.

Last December, seismic and infrasound networks caught the moment of collapse. “But we have many volcanoes around the world where there are no such stations nearby,” Dr Walter said. “We should look at those volcanoes where there is a risk of sector collapse and invest in a densification of instruments.”

The GFZ volcanologist’s team has published its findings in the journal Nature Communications.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos