Facial analysis can provide meeting professionals with a moment-by-moment snapshot of the overall emotional response of groups of meeting participants. (Whatever Media Group)

Trying to assess how someone feels from their facial expressions “can be tricky,” said Panos Moutafis, the cofounder and CEO of tech company Zenus. “It is very hard to read people,” he said, “especially when you talk about complex emotions.” For example, when he talks to investors about his company, which offers services including collecting data about audience engagement based on factors including facial analysis, it’s often those who listen with only the slightest expression on their faces who are the most likely to invest, he said.

But measuring the overall sentiment of a group of people does provide meaningful feedback, said Moutafis, who founded Zenus a decade ago. Sometimes called emotional AI, the technology uses sensors, combined with AI, to analyze second-by-second changes in both physical movement and facial expressions of groups, including in airports, retail environments, events, and other social spaces. In recent years, Zenus’s technology has been used at conferences and trade shows, including IMEX Frankfurt, IMEX America, IAEE’s Expo! Expo!, and PCMA Convening Leaders.

Panos Moutafis, cofounder and CEO of Zenus

Zenus labels its product “ethical facial analysis,” and Moutafis uses precise language when he describes the technology his company has developed — the use of facial analysis has been criticized as a violation of the privacy of meeting attendees, particularly when event organizers haven’t been upfront about the fact that the technology is in use. People often conflate facial analysis with facial recognition, the latter of which uses image data to identify individuals, Moutafis said. Unlike facial recognition, facial analysis has been developed by Zenus in a way that “does not record or retain any personal information — no video, no images, no names, no unique IDs, anonymized or otherwise.” Although it is not illegal to use the technology that way in public spaces, Moutafis added, he always recommends that event organizers and other clients are transparent with people about its use.

Taking Emotional Score

The data Zenus collects is behavioral — measuring, for example, the number of people in a space and how that number goes up and down over time — and experiential. By collecting and analyzing facial expressions, Zenus provides moment-by-moment snapshots of the overall sentiment of groups of participants, expressed with a numerical score. “It’s a tool that helps you analyze, on a continuous scale and on a very detailed level, what stimuli creates an effect on people’s emotional response on a group level,” Moutafis said. For example, “when you see that somebody on stage talked about technology and everybody’s faces were excited, that’s a signal that this was a topic that created some excitement.” On the flip side, he added, if a speaker at a medical meeting is talking about poor patient outcomes, the fact that “faces are less expressive or sad or troubled, and you have a lower energy in the audience, that doesn’t mean that the session content is bad. It means that the topic created a certain emotional response to the audience.”

When a lot of people react in the same way in a certain moment, “then it starts to become a validation process,” said Nick Borelli, marketing director for Zenus. But collecting the data just to collect data will not do you any good, he said. “You need to have a strategy of what you’re going to collect, why you’re collecting it, and how you’re going to use it afterwards.”

In many instances, the goal isn’t simply to maintain a high positive sentiment score. Sometimes a lower sentiment score “is a good score because you want people’s energy to slow down,” Moutafis said. At an activation at IMEX last October, for example, a violinist played calming music in a corridor, Borelli added. “This is where the energy scores were lower by design. They want people to decompress.”

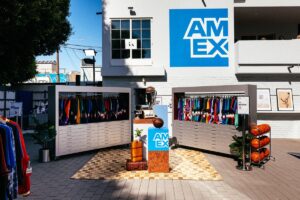

The demand for facial-analysis data collection at trade shows and sponsorship activations is growing year over year, according to Zenus’s Panos Moutafis and Nick Borelli as well as Louis Layton, Freeman’s director of digital products. (Whatever Media Group)

The data that Zenus collects about engagement can be applied to specific demographic groups within an audience, including by age and gender, Moutafis said. The ability to accurately categorize participants in those groups isn’t 100 percent accurate, Moutafis added. It is not uncommon, he said, for up to one out of five faces at an event to not be included in demographic categories. “But when you have so many faces, so many people over a long period of time, you get enough of a sample size” to be confident about the overall response, he said.

The data can reveal patterns, including what topics most resonate with different demographic groups and provide clues that can help identify solutions to problems when combined with other data. For example, at one medical meeting, facial analysis showed that women under 40 were highly engaged throughout the event, with the exception of during educational sessions, Moutafis said. “When the organizer analyzed the speaker lineup, they realized that women that age weren’t represented.” And, after the organizer made changes to speakers to include more women who are younger, “not only did the engagement levels go up for women” who were identified as under the age of 40, he said, “it went up for the entire audience.”

‘Different Pieces of the Puzzle’

Because facial analysis has the capacity to passively collect information about a large percentage of an audience, “people come to us all the time and say, ‘My active data collection in polls is 2 percent of the people — you’re getting everybody,’” Borelli said. “And we say, ‘Yeah, but please don’t get rid of your polls.’”

The strength of a survey, Borelli said, is that it gives people “the opportunity to express themselves verbally: ‘I like this. I don’t like this. This speaker was great because they talked about that.’ That’s a very big advantage of surveys — you get a lot of contextual information … They’re the clues that make the passive data collection make sense.” And it’s not just surveys that help make the data more meaningful, he said. “It is the on-site observations and the direct feedback conversations. They are different pieces of the puzzle, and the more pieces you have, the clearer the picture you’re looking at.”

When Convene spoke with Moutafis and Borelli, and with Louis Layton, Freeman’s director of digital products, all three stressed the growth in demand for facial-analysis data to be collected at trade shows and sponsorship activations. The ability to receive real-time feedback allows exhibitors and sponsors to make immediate changes to variables such as the content of digital banners or booth staffing levels, and to fine-tune their strategies to fit their goal, based on participants’ responses.

The data can challenge conventional wisdom — and validate the power of emotion. One example, Borelli said, is the handouts that sponsors sometimes give at activations. “When you study the behavior and the emotional response of groups of participants,” he said, “you might see a spike in excitement, but a very short dwell time, meaning you create excitement, but not for long,” he said. On the other hand, activations that speak to people’s hearts, like treatment for cancer patients or puppies elicit very emotional reactions, he said. “Puppies are an extreme — you see very big responses and very long dwell times. You know this resonates and people are going to talk about it.”

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor at Convene.

Everything You Need

Everything You Need

to Know About ROE

This article and those listed below are part of Convene’s April 2025 issue cover and CMP Series story package.

Everything You Need

Everything You Need