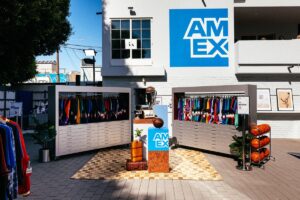

A rendering of the planned redevelopment of the Austin Convention Center, which will make a connection to Waterloo Greenway, a chain of parks and public spaces located downtown. Courtesy LMN/Page Joint Venture

The standards set by the International Living Future Institute’s (ILFI) zero-carbon certification program are some of the most stringent and ambitious in the world. Living Future’s aim is not just to create energy-efficient structures that reduce the environmental costs to operate them, but, according to its website, are a positive force for climate response.

To date, 122 buildings around the world have registered as having followed ILFI zero-carbon certification standards, but only 11 have been certified, including the Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle. It’s a high bar, said Leo da Costa, a principal at the Seattle-based LMN Architects, which is designing the redevelopment of the Austin Convention Center now underway in Texas, along with Page, a global architecture and engineering firm. The $1.6-billion project, scheduled to open in four years, is planned as the first zero-carbon convention center in the world, da Costa told Convene. Once open, buildings must undergo a year-long verification process by a third party to achieve certification.

ILFI, now based in Seattle, was launched in 2009 by Cascadia Green Building Council, now the Cascadia Green Building Coalition, a British Columbia-based nonprofit. One of the things that sets the ILFI certification standards apart from other programs, including LEED, is that the zero-carbon certification considers the greenhouse gas emissions associated with all aspects of a building and its materials, including the extraction of raw materials, their manufacture, transportation, use, and disposal — also referred to as “embodied carbon.”

According to the World Green Building Council, buildings and construction are responsible for 39 percent of global energy-related carbon emissions. Of this, 11 percent is attributed to materials and construction processes, and the remaining 28 percent comes from operational emissions like heating, cooling, and powering buildings. Among the requirements of the ILFI zero-carbon certification is that buildings reduce embodied carbon emissions by 20 percent, a goal that the Austin Convention Center project designers will help meet by reusing materials from the existing convention center that they are replacing.

“We’re really familiar with that project and its materials and its structural design,” said Josh Coleman, the design director and principal at Page, which was founded in Austin in 1898. The company designed the convention center that opened in 1992, as well as a subsequent renovation, which “really gave us a leg up in trying to figure out what materials can we deconstruct from that building and reuse in the new facility,” he told Convene.

Some of the materials that will be reused will be visible, such as an expanse of sunshades made of blue glass and bat-shaped bicycle racks, but others will not, including 60-foot-long steel trusses that will be part of the new building’s structural system. Construction of the new center, which will almost double the size of the previous center, will use low-carbon materials sourced as close to downtown Austin as possible. For example, the trusses that will span a column-free, 80,000-square-foot ballroom will be made of mass timber, a load-bearing building material made from layers of wood — which, in this case, will be southern yellow pine, a species native to Texas.

ILFI’s zero-carbon certification guidelines require that new buildings operate using renewable, rather than combustion-based, energy. “One of the things that the convention center is committing to is all-electric operations,” including kitchen equipment, da Costa said. The center plans to purchase carbon-free energy through the city-owned Austin Energy’s GreenChoice program, he said. In September 2021, Austin’s city council adopted the Austin Climate Equity Plan, which includes the goal of reaching net-zero community-wide greenhouse gas emissions by 2040.

Although the ILFI standards are strict, the project has applied for and received one exception to the no-combustion requirement. “We are getting a cultural accommodation for our outdoor wood-fired barbecue,” Coleman said, “because the convention center needs to serve barbecue in Austin. They’ve acknowledged that that’s a part of our culture — we thought that was cool.”

A Natural Connection

The redevelopment of the convention center offered designers a chance to rethink the convention center site in relationship to the rest of downtown, da Costa said. Where the existing center occupied six full blocks of the city’s footprint, the new design will break up the previous big-box profile into distinct blocks that reconnect the city’s grid and reflect the flavor and culture of Austin’s surrounding neighborhoods, he said.

That includes making a connection, through outdoor terraces and walkways, with Waller Creek, which traverses downtown Austin and touches the convention center’s east side. The creek channel, once heavily eroded by floods, has been reconstructed, restoring habitats for wildlife, native plants, and trees. The creek is part of the Waterloo Greenway, an ongoing project that is creating a one-and-a-half-mile-long chain of parks and public spaces downtown.

The design aimed at creating “something that felt more seamless,” da Costa said, “so you don’t have a big transition between what they’re doing on the creek project side and what we’re doing on the convention center side. The idea was to provide that sense that there’s a natural environment here that continues around that edge of the creek — almost as if it is part of one big experience.”

And being that this is Austin, “where we get a lot of hot weather and our sun is really strong,” Coleman said, “all those choices work really well, too, with the solar orientation. It’s a little bit cooler, a little bit more hospitable, on the east side than it is on the west side where we get that late-afternoon hot sun. … Obviously, we have very high sustainability goals, so we’re really trying to think about all these things together as we make decisions.”

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor at Convene.