A rendering of the new Austin Convention Center highlights its immersion in nature. Courtesy LMN/Page Joint Venture

Nearly 15 years ago, in a Convene story about the future of convention centers, architect Mark Reddington, a partner at Seattle-based LMN Architects, said that as the trend toward integrating convention centers with their surrounding urban landscape deepened, “we may also see the convention center become more fragmented, broken into discrete pieces and distributed into the texture of the city.”

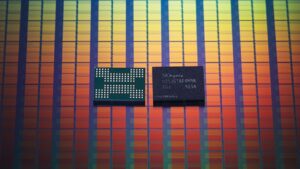

The renderings of the planned reconstruction of the Austin Convention Center bring Reddington’s predictions to life — instead of one monolithic building covering the six-block convention center site, the project will be broken into distinct parts. Each will have its own character and personality, reflecting the surrounding Austin neighborhoods, said Leo da Costa, a principal at LMN Architects, which along with Page, a global engineering and architectural firm, is designing the new convention center.

The $1.6-billion project, now underway and scheduled to open in four years, offered designers a chance to rethink the convention center in relationship to the city, said da Costa. The center is being built to the zero-carbon standards set by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), which sets stringent guidelines for use both in the construction and operation of the building. (See “Will This Be the Greenest Convention Center on the Planet?”)

But ILFI’s standards go beyond minimizing carbon emissions in the physical realm — the material resources and energy that go into building and running a building — and are intended, according IFLI’s website, as a call to action for governments, urban planners, developers, and others to use architecture and landscape design to create communities that are as connected as natural ecosystems.

Architects made a pivotal decision to move some of the very large, contiguous space that convention centers require — an exhibition hall, along with adjacent loading docks —underground. Once you do that, he added, “you have a lot more flexibility on the ground level. What we decided to do here was this idea of reconnecting the existing grid of the city,” restoring some of the texture and rhythm that contribute to a city’s street life, he said. By breaking the scale of the building and reconnecting the city’s grid, the center will be “something that feels more appropriate to the scale of Austin and more inviting, I think, to people.”

The team working on the newly redesigned Austin Convention Center aimed at creating “something that felt more seamless.” Courtesy LMN/Page Joint Venture

For example, Second Street, a thriving district filled with locally owned restaurants and businesses, will extend into the convention center site by way of a pedestrian-only corridor, the Paseo. It will serve as a “thoroughfare through the building, controlled by the center and built to the scale of a city street,” da Costa said. The convention center also will use a variety of building heights and materials to “stitch together” Austin’s diverse surrounding neighborhoods, said Josh Coleman, design director and a principal at Page. On the west side, toward Second Street, the façade will be brick, like many of downtown Austin’s historic buildings. “We wanted to take a little bit of that urban character and carry that inside the building,” da Costa said.

“We really pushed our design concepts,” he added, by setting a project goal that the people who come to the building will feel like they are experiencing some of the things found in other parts of the city. That includes the center’s 70,000 square feet of outdoor event space, which is meant to mirror Austin’s indoor-outdoor culture, such as the nearby Rainey Street district, where bungalows have been renovated as bars and restaurants and the streets are lined with beer gardens and food trucks.

“Everybody knows SXSW” — which was founded in Austin as a music festival in 1987, and now annually attracts thousands to the city for a greatly expanded event — Coleman said. “It’s a big, big fun event every year. And if you look at their roots, going back to the late ’80s, they had an event that was distributed — they were in all those historic, storied music venues up and down Sixth Street” and throughout downtown, he said. “That resonated with us, too. We have a convention center that has a fixed site, but we are very interested in this idea of varied experiences, influenced by where you’re at on our site.”

Connected to Nature

Much of the outdoor space will be on the center’s east side, the designers said, where outdoor terraces and walkways will make a connection with Waller Creek, which traverses downtown Austin. The creek is part of the Waterloo Greenway, an ongoing city project that is restoring natural habitats and creating a one-and-a-half mile-long chain of parks and public spaces downtown.

The design is aimed at creating “something that felt more seamless,” da Costa said, “so you don’t have a big transition between what they’re doing on the creek project side and what we’re doing on the convention center side. The idea was to provide that sense that there’s a natural environment here that continues around that edge of the creek — almost as if it is part of one big experience.”

And being that this is Austin, “where we get a lot of hot weather and our sun is really strong,” Coleman said, “all those choices work really well, too, with the solar orientation. It’s a little bit cooler, a little bit more hospitable, on the east side than it is on the west side where we get that late-afternoon hot sun. … we have very high sustainability goals, so we’re really trying to think about all these things together as we make decisions.”

“The project has the potential to really transform this part of downtown Austin. And we firmly believe that by making this a better neighborhood, with a better set of streets and sidewalks around it,” da Costa said, the convention center “is going to improve the experience of the attendees who go there for an event — and also for the people who live and work in the city.”

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor at Convene.