Nasa’s IceSat space laser tracks water depths from orbit

The US space agency’s new polar observer could have a transformative impact in an unexpected area. …

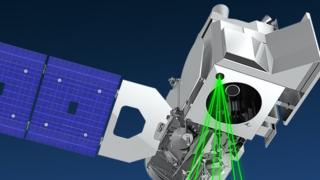

Image copyright NASA

Image copyright NASA Scientists say one of the US space agency’s (Nasa) new Earth observers is going to have a transformative impact in an unexpected area.

The IceSat-2 laser mission was launched a year ago to measure the shape of Antarctica and Greenland, and to track the thickness of Arctic sea-ice.

But early results show a remarkable capability also to sense water depths.

IceSat’s laser light penetrates up to 40m in the clearest conditions, opening up a raft of new applications.

“As much as people think all areas on Earth have been reasonably well mapped, it’s really not true when you start looking at shallow water areas,” said Dr Christopher Parrish from Oregon State University.

“We’ve got huge data voids from the shoreline out to about 5m water depth.

“This hinders our ability to study things like inundation, the effects of major storms, and the changes to coral reef habitat.”

A project has already started to map the seafloor around low-lying Pacific islands and atolls, which will assist tsunami preparedness for example.

The capability should also enable scientists to work out the volumes of inland water bodies to help quantify Earth’s global freshwater reserves.

IceSat-2 was launched in September 2018 with just the single instrument – a half-tonne green laser called Atlas that fires about 10,000 pulses of light every second.

Each of those shots goes down to the Earth and bounces back up on a timescale of just a few milliseconds. The exact time equates to the height of the reflecting surface.

Scientists knew they could use this optical “tape measure” to look for elevation changes in Antarctica and Greenland that might indicate melting.

Assessing forests was also part of the mission objectives because the laser will reflect off canopies to reveal tree heights.

But quite so prominent a role for bathymetry (the mapping of underwater topography) was not expected.

“Before launching IceSat-2 we flew an aircraft instrument called Mable, which had a lot of the same measurement characteristics, and we did see some bathymetry but only down to a couple of metres,” recalled Nasa’s Tom Neumann.

“So before launch when people asked me about what IceSat-2 could achieve I said ‘let’s wait and see’.

“But the optics in Atlas have better efficiency than the specifications; we’ve exceeded the performance requirements. And so folks like the US Coast Guard and the US Geological Survey are interested in the data because you now have the ability to measure near-coastal bathymetry, essentially worldwide.”

There are obvious limitations. The more turbid the water, the more difficult it is to get a laser reflection from the seafloor. And, of course, this kind of laser technique is of no use in the open ocean where depths can reach 6km or more.

Also, because the satellite is geared towards polar mapping, its orbital path means mid- and low-latitude regions of the Earth are sampled less frequently.

But it’s not necessary to have completely full coverage across an area. That’s because one IceSat track through a scene can be used to calibrate other information.

“What people are doing is using visual imagery from other satellites which will give you a relative depth,” explained Dr Neumann.

“So the deeper the blue colour, the deeper the depth; the lighter the blue, the shallower it is. And then you combine that with an IceSat track and that gives an absolute measurement across that scene.”

In the Antarctic and the Arctic, this is being used to look at meltponds – the large bodies of meltwater that form on ice surfaces in the warmer temperatures of Summer.

The volumes involved can be prodigious and can affect the stability of the ice, either speeding its flow to the ocean or, in some cases, helping to break it apart. With IceSat-2 scientists can now say more precisely how much water is sitting on top of the ice.

Prof Helen Fricker from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography has been testing this approach over the Amery Ice Shelf, the third largest ice shelf in Antarctica.

She sees it as another variable to monitor climate change at the poles.

“It’s important to keep track of how much surface meltwater is being produced every year. The other thing to keep track of is the timing – when the melting starts and when the meltwater refreezes at the end of the season. Also the locations of meltponds: are they changing? Are they moving further north with time?”

To mark the one-year anniversary of IceSat-2 launch, mission scientists have published a review of achievements to date in Eos, the weekly magazine of the American Geophysical Union.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos